We recognise the continuous and deep connection to Country, of Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander peoples as the first peoples of this nation. In this way we respectfully acknowledge the Traditional Custodians of this land, sea, the waters and sky. We pay tribute to the Elders past and present as we also respect the collective ancestry that has brought us all here today.

AUTHOR: JULIE BAKER

With over 15 years of experience in internal audit I have gained firsthand insight into the transformative role of internal audit. My current role is at Sententia Consulting in the internal audit service line and previously I held a Chief Audit Executive (CAE) equivalent role in the ACT Government. My passion for the profession stems from the powerful impact we have in enhancing organisational processes and offering invaluable insights into the health of an organisation.

The introduction of the new Global Internal Audit Standards (the Standards), effective January 9, 2025, marks a significant milestone for the internal audit profession. These Standards add a new layer of rigor to our profession and underscore the importance of maintaining the highest standards of professionalism in our work. As internal auditors, it is crucial that we not only understand these changes but actively embrace them to fulfill our obligations.

In this article I explore two key components that not only highlight important changes but also reflect the evolving demands placed on CAE’s to shape the future of the internal audit function

CAE Reporting to the Board and Senior Executive

One of the most prominent changes introduced by the Standards is the expanded scope of CAE reporting to the Board and Senior Executive. Historically, CAEs have reported critical aspects of the internal audit function, including:

- The Internal Audit Work Program (IAWP)

- Budget management

- Audit Charter

- Any disagreements between the CAE senior management on scope, findings or other aspects of the engagement, among other things.

However, the new Standards require CAEs to include additional elements, such as:

- The IAWP discussions with the Senior Executive

- Evaluating the adequacy of resources, including technological resources, and strategies to address shortfalls

- CAE qualifications and competencies

- Developing an Internal Audit Strategy that outlines future direction.

These new requirements provide an opportunity to further elevate the professionalism and transparency of the internal audit function. However, they also introduce new challenges – particularly in how we engage with the Senior Executive. Below is my take on these requirements from the perspective of a CAE.

Discussing the IAWP with the Senior Executive

As a CAE, I have witnessed firsthand the impact that discussions with Senior Executives can have on the independence of the IAWP. I have found that Senior Executives and Branch Heads often provide a mix of valuable insights into topics, but they may also suggest their own area not be audited or provide reasons for delays. More importantly if Senior Executives expect they can shape the IAWP, it can jeopardise its independence. To maintain independence, I recommend an IAWP process that includes:

- Interviewing Senior Executives (including branch heads) to gather potential IAWP topics.

- Compiling and ranking the suggested topics with the input of external Audit and Risk Committee (ARC) members.

- Submitting the draft IAWP, based on ARC members rankings for discussion at the ARC.

- Finalising the IAWP based on the ARC’s feedback.

By clearly defining the role of the Senior Executive in IAWP discussions it is possible to gain valuable insights into specific topics across the organisation, while safeguarding the independence of the IAWP.

Evaluation of resources and addressing shortfalls

The Standards include a requirement for CAEs to carry out an evaluation on resources with a strategy including how to address shortfalls. A common tension for CAEs is managing limited resources while delivering the IAWP. Whether it is technological tools or personnel, this balance can be challenging. In my experience, resource shortfalls were better addressed through managing expectations rather than seeking additional funding.

I focused on optimising existing resources, managing what I had and taking a proactive approach to avoid shortfalls in audit delivery. Resource allocation began with the number of audits in the IAWP and budgeted days. Some audits were high level and others deep dives. My scopes were broad, budgets modest, the topics complex and the time to carry out the work was limited. I had a

government panel of providers that expanded from 7 to 12 service providers.

Methods I used to optimise audit outcomes within existing resource levels included:

- Sending requests for services (RFS) to a group of providers with prior knowledge of the organisation as this knowledge is beneficial.

- Carefully evaluating submissions to ensure the offer clearly aligned with my needs and proposed staff were appropriately experienced.

- Attending entry and exit meetings and always listening to all contributions with a lens of improving practices across the organisation.

- Holding a preliminary meeting with the assigned service providers prior to exit meetings with business areas to understand progress and findings and ensure the scope had been fully addressed.

- Reviewing the draft report before it was distributed more broadly, ensuring it could be understood by readers unfamiliar with the content and that recommendations were beneficial and allocated to the right section to support a smoother review process with business areas.

For me, these practices were requirements for all internal audit reports, regardless of the budget, to support clear oversight and enable the management of expectations to get quality outcomes with limited resources.

From a broader perspective, addressing technological resource gaps does not necessarily mean acquiring bespoke internal audit tools. When relying on outsourcing internal audits to service providers, the service providers use the internal audit tools available to them. When performing in-house internal audits, the tools available within the Microsoft Office suite are usually sufficient to manage the process when used effectively, demonstrating that technological resources do not have to be elaborate. Regardless of the resources available, the key to overcoming technological

resource challenges is utilising what is available and communicating with senior leadership regarding what is realistically possible.

CAE qualifications and competencies

Another significant change is the reporting of CAE qualifications and competencies to the Board and Senior Executive. While qualifications and competencies were always an expected part of the CAE role, they were not typically reported to the Board. The new Standards suggest the Board approve the CAE’s job description and encourage pursuit of opportunities for continuing professional education,

membership in professional associations and opportunities for professional development.

This shift raises important questions about the role of professional development and the value of qualifications versus on-the-job competencies. It seems to me that these suggestions imply that if competencies were the reason for the CAE appointment, then there is an expectation qualifications would follow. From my experience, CAE qualifications are an important factor in establishing credibility, but the ongoing development of competencies is equally critical. The Standards suggest that Boards encourage continuous professional development, which is a positive step toward fostering a culture of learning and growth within the internal audit function.

The requirement to report CAE qualifications and competencies to the Board leaves me wondering what form this could take. I see delivery of the IAWP, including the quality of the internal audit reports and secretariat function as practical measures of the competencies.

Would the reports include:

- A CV listing CAE qualifications and work experience.

- The CAE’s ability to resolve action items from ARC meetings

- On the job training provided to the team

- A combination of all these factors?

Would it be self-reporting? Or would it be a survey of key stakeholders like the Board Chair, Senior Executives, selected service providers and the internal audit team? Consider the scenario, given the bias often held against internal audit – How would recommendations that improve practices across the organisation, but increase the workload for a Senior Executive be reflected in a CAE competency review?

It is my view that all these considerations would need to be factored in to make reporting CAE qualification and competencies have real value.

Developing an Internal Audit Strategy to deliver the Internal Audit Work Plan

One of the new requirements in the Standards is the formal expectation for CAEs to develop an Internal Audit Strategy that aligns with the organisation’s strategic objectives. This strategy should detail how the IAWP will be delivered and ensure that the internal audit function supports broader organisational goals.

When I was first tasked with developing an internal audit strategy, it was at the

request of a five-year external assessment of my internal audit function. Once I created the strategy, it became an invaluable tool for guiding the internal audit function and ensuring that the team was aligned with both internal and external expectations.

My strategy included elements such as:

- Vision and mission for the internal audit function

- Delivery methods (including the management of external service

providers). - Timelines for IAWP, Charter review and approvals and financial

statement reviews - Budget management processes and tracking

- Recommendation implementation tracking and reporting

- The Board Secretariat.

While my internal audit team was relatively small, creating a strategy helped ensure that team members understood their roles and expectations. It also made it easier to communicate with senior management and the Board, fostering a more transparent and collaborative relationship. Now, with the new Standards, this strategic approach is a requirement for all CAEs, regardless of the size of the

internal audit function. Embrace the strategy as a beneficial, centralised document containing the internal audit function deliverables.

Act Now

The new Standards present both opportunities and challenges for CAEs. The expanded reporting requirements and the development of an Internal Audit Strategy are essential for ensuring that internal audit functions are aligned with organisational goals and are delivering value. However, these changes also require careful thought, especially regarding the independence of the IAWP, resource

management, and the reporting of qualifications and competencies.

As CAEs, we must be proactive in understanding and implementing these new requirements. The Standards provide an opportunity to further elevate the internal audit profession and demonstrate the value we bring to organisations. By embracing these changes and leading the internal audit function with transparency, professionalism, and foresight, we can build stronger relationships with governance bodies and enhance our ability to add value to our organisations.

It’s time to act now—to align ourselves with the new Standards and ensure our internal audit functions are equipped for success. Let’s take this opportunity to advance our profession and continue to drive meaningful impact in the organisations we serve.

If you would like any additional information contact Sententia Consulting on Sententia@sentcon.com.au.

AUTHOR: KIRSTY WISDOM

It’s internal audit program planning season! As internal audit consultants we get the opportunity to work with a variety of diverse organisations auditing a wide range of different topics. This gives us unique insight into trending topics and common issues that might be worth considering for your organisation.

If you’re working in the public sector, it will probably come as no surprise to you that areas like integrity, climate change risk management, third party risk management, information management, artificial intelligence, and conflicts of interest are finding their way onto a lot of audit programs – and for good reason. These are areas of emerging risk and increasing public scrutiny that are timely to seek some assurance confidence over. Here we outline some the common pitfalls that are worth considering when auditing these trending topics and how to avoid them.

Integrity

Across the broader Australian Public Service (APS), there has been a marked increase in the attention and emphasis directed toward the concept of integrity. This focus was initially driven by the Independent Review of the APS (the ‘Thodey Review’) in 2018 and is central to the current APS reform agenda which includes a priority area focused on promoting “an APS that embodies integrity in everything it does”.

Everyone knows that integrity is a hot topic, but the main pitfall we see is simply uncertainty about how to actually embed it, and even more uncertainty about how to provide assurance over it. For agencies that have started to dip their toe in the water of auditing integrity, the initial focus tends to be on assessing whether good policies/procedures/training etc. are in place – i.e. – “are we saying the right things?”. This is an important place to start, but the real challenge comes in understanding whether people are doing the right things and acting with integrity in practice.

Starting small with a relatively high-level framework-based review will still deliver value. Auditing integrity in any way helps to demonstrate that it is an organisational priority and will start to get people thinking about what it means to be held to account for an integrity culture. To get the most value out of this type of review, it is important to consider how well messaging is tailored to the actual organisational context (and the different contexts within the organisation) to support staff to understand integrity as an everyday consideration rather than an abstract concept.

But to start to get assurance over the integrity culture in practice, auditors need to consider broader techniques such as surveys, staff interviews, focus groups, behavioural observation, and business context analysis. This too can start relatively high level to get initial insights and inform future planning for more targeting reviews. Where integrity culture is a high priority and higher assurance confidence is desired, a more robust and repeatable program of integrity culture audit can be developed. To get value from these more comprehensive audits, it is crucial to define and agree what a good integrity culture looks like for that organisation, including key desirable and undesirable behaviours, to provide a consistent baseline against which to compare.

Climate change risk management

The introduction of climate disclosure reporting requirements for Commonwealth entities has boosted climate change risk management up the agenda from an assurance perspective. The main pitfall we’ve noticed in this case is a focus purely on ensuring preparedness for compliance with the new requirements. Although this is important, internal audit functions should take this opportunity while climate risks are front of mind to promote and explore other aspects of climate risk management that are important organisational considerations.

Depending on the nature of the organisation, additional aspects that should be considered include how climate risks may impact Work Health and Safety, Business Continuity Planning, and Disaster Recovery Planning. Have these policies and the associated risks and controls been re-assessed in light of a changing climate and more regular extreme weather events? Does the organisation have clear rules and guidance in place around things like extreme heat and are these understood and implemented in practice?

More broadly, have climate change risks been considered strategically where they may have a direct impact on agency goals? Have these risks been factored in as part of development of strategies and goals, and are they considered on an ongoing basis? The nature of these risks will vary greatly between organisations, but there are potential impacts to consider across health and social outcomes, infrastructure, productivity, service delivery and more that will be relevant for various public sector agencies.

In considering climate change related risks, specific expertise is generally required to ensure an audit is sufficiently robust to provide more than surface level insights. Such expertise supports the audit team to more effectively challenge management assumptions were needed and ensure risks are fully understood and nothing is missed. For this reason, including a subject matter expert as part of the audit team is crucial to ensuring value.

Third-Party Risk

Outsourcing, shared services, and reliance on third-party providers are now entrenched features of federal government operations. Whether it’s IT infrastructure, defence procurement, health services, or consulting engagements, third parties are often integral to delivering core functions. However, although you can outsource services, you cannot outsource risk.

The key pitfall we come across in auditing third-party risk is confusion around the concept itself and who is actually accountable and how these risks can and should be managed. Unfortunately for the public sector, the public don’t much care for excuses. Even if the issue was 100% the fault of the third party – how could the government have allowed this to happen? Why weren’t you monitoring it? Why didn’t you do your due diligence? Again, you cannot outsource your risk.

Third-party risk is multifaceted – spanning performance, cyber security, ethical conduct, compliance, data privacy, and financial integrity. Failures by external partners can have significant consequences for service delivery and public confidence.

As a result, internal audit must ensure that third-party governance frameworks are robust, including due diligence processes, contract management practices, and monitoring mechanisms. This also extends to sub-contractors, where transparency and accountability may be further diluted. Third-party risk is a crucial topic to audit to help agencies understand their risk profiles and identify improvement opportunities. Auditors can add further value by treating stakeholder engagement throughout the audit process as an opportunity to educate on accountabilities and expectations to support improved understanding and risk culture as this capability gap tends to be the main barrier to strong third-party risk management.

Information Management

Information is one of the most valuable assets in the modern public sector. Information management refers to the creation, description, preservation, storage, protection, usage, disposal, and governance of digital and non-digital records and data that are relevant to the operation of an entity. Good information management maximises the value of an agency’s information assets by ensuring they can be found, used and shared to meet government and community needs and support the efficient and effective delivery of outcomes.

This is relatively well understood across the public sector, and as a result, information management is a regular feature on audit programs. There are plenty of useful and detailed standards that can be applied such as the Information Management Standard for Australian Government which align to obligations under the Privacy Act and Archives Act that make for a relatively straightforward audit. But there is one crucial element that these “straight forward” information management audits ignore – people. In our experience, the biggest risks from an information management perspective are not systems, but people. We’ve seen agencies with world class systems and processes and well-tested system controls – where staff save everything offline on their desktop and make endless use of workarounds to avoid ever having to touch that world class system.

This human side of information management is crucial to consider in the design and delivery of an information management audit to get a true understanding of risk levels and effectiveness.

Conflicts of Interest

Conflicts of interest, whether real or apparent, can undermine the credibility of government decisions. In a public sector context, where impartiality is paramount, even the perception of bias or favouritism can erode trust. From procurement panels to grant allocations and recruitment decisions, conflict of interest risks can be found across everyday government operations. Recent scrutiny around conflicts of interest in the public sector has pushed COI onto the agenda for many audit committees.

There are some common pitfalls we have noticed that should be considered when scoping an internal audit. Most agencies have a decent COI Policy, with COI built into annual training programs – but this is really the bare minimum. Implementation and truly embedding understanding of COI into business as usual is where it tends to come unstuck.

For example, it is worth remembering that the relevant requirements under the Public Governance Performance and Accountability (PGPA) Act, and PGPA Rule are mostly not framed around conflicts of interest, but rather disclosure of any material personal interests. The intent is to manage real or apparent conflicts – but a lot of agencies seem to place such a focus on conflicts that they forget that disclosure requirements relate more broadly to any material personal interests.

As a result, material personal interests tend to only be considered in individual contexts in case there is a potential conflict there. Disclosure processes are often completely disjointed or siloed with no central repository or visibility across the organisation. But the people making the disclosures don’t always know that and often assume if they have disclosed an interest in one place for one purpose, then they have ticked off on their duty.

In auditing conflicts of interest management, particular attention should be paid to whether/how personal interest declarations are managed holistically. Additionally, it is very difficult to audit whether appropriate interests have been declared – as auditors simply don’t know what they don’t know. We can audit whether declarations that have been made have followed appropriate processes, but what about declarations that weren’t made? An element of culture-based audit utilising techniques like surveys or interviews can be useful to provide additional insight on this aspect.

Artificial Intelligence (AI)

AI is the word on everyone’s lips as the power and prevalence of the technology continues to expand. In the public sector, there are rightly concerns around how and when AI can or should be used while maintaining integrity, protecting privacy, and meeting community expectations and legislative obligations (noting that most program legislation was not drafted to cater for AI). However, most agencies are already using AI in some capacity and planning to increase usage. As a result, audits of AI governance are popping up as a high priority.

Drawing on recently released whole-of-government guidance like the Australian Government Policy for the responsible use of AI in government and the Australian Government AI Assurance Framework, audits tend to focus on agency policies and governance arrangements for the design, development, deployment, monitoring and evaluation of agreed use cases.

Although this is of course crucial, a key element that is not always captured or considered are the unapproved use cases that the agency might not even be aware of as staff look for ways to increase efficiency in their day-to-day workflows using publicly available tools. Internal Audits of AI governance should include consideration of broader AI culture across an agency and how risks around “shadow AI” from unauthorised individual use cases are understood and mitigated.

The Sententia Consulting team recently traded laptops for sunhats and headed to beautiful Manly for our annual company retreat — and this year, it was something truly special.

Framed by blue skies and golden beaches, our retreat provided more than just a change of scenery. It offered a rare and valuable opportunity to pause, reflect, and reconnect; not only with each other, but with the values and vision that continue to drive us forward. From the moment we arrived, it was clear this wasn’t just another offsite, but rather a celebration of how far we’ve come, and a springboard into everything that lies ahead.

![]()

Marking a Milestone: 5 Years of Sententia

This year holds particular significance for our firm as we celebrated five years in business — a major milestone that reflects not only the success of our work, but the passion, trust, and dedication of every single person who has been part of our journey. In an industry that’s constantly evolving, reaching the five-year mark is a meaningful reminder of the strength of our foundations and the clarity of our vision. It’s been five years of building relationships, delivering impact, and growing a business that we’re genuinely proud of.

Welcoming New Faces, New Ideas

As a fast-growing firm, one of the most energising aspects of this year’s retreat was the presence of so many new team members. Over the past year, we’ve welcomed a number of talented individuals into the business — each bringing fresh perspectives, diverse experiences, and new energy to our work.

The retreat created space for these new connections to form organically. Whether it was over strategy sessions, team-building exercises, or beachside coffees, it was inspiring to watch people from different parts of the business come together, share ideas, and start to shape our next chapter. Moments like these are when culture is built — not through policies or slogans, but through genuine human connection.

![]()

![]()

Reflecting, Realigning, Recharging

A core part of our retreat was taking time to reflect on where we’ve been, where we are now, and where we’re going next. Through facilitated strategy sessions and open team discussions, we explored our vision for the future and aligned on the big goals ahead.

These conversations weren’t just about strategy documents or quarterly objectives — they were about values, impact, and how we want to show up for our clients, our communities, and each other. In the fast pace of day-to-day work, it’s easy to focus on outputs. But this retreat reminded us of the importance of stepping back to focus on why we do what we do, and how we do it together.

Building with Purpose: Our Partnership with the WaterWorks Program and Pinnacle

One of the most memorable and meaningful parts of the retreat was a hands-on team-building session facilitated by Pinnacle and the WaterWorks Program. During this session, our team collaborated to build six emergency water filters — each one destined for a community in Uganda where access to safe, clean drinking water remains a daily challenge.

This wasn’t just a powerful team exercise — it was a tangible reminder of how our efforts, even from afar, can make a real difference. Each filter we constructed has the capacity to provide clean water to a family for up to five years. To know that something built with our own hands could help protect the health and dignity of others around the world added a deep layer of meaning to our experience.

In addition to the emergency filters, Sententia Consulting has also contributed to the installation of permanent water filtration systems in Uganda — supporting longer-term access to safe water across several communities. These initiatives align with our belief that businesses have a responsibility to create positive impact beyond profit.

Pictured: Sententia employees participating in the WaterWorks team building exercise, building water filters while blindfolded.

A Surprise to Remember: Cruising Sydney Harbour

Just when we thought the retreat couldn’t get any better, the team was surprised with an unforgettable evening: a private chartered boat on Sydney Harbour to celebrate our five-year milestone in style.

As the sun set over the skyline, we shared drinks, stories, and laughter on the water, taking a moment to breathe in the beauty of the city and the significance of what we’ve built together.

A huge thanks to Karisma Cruises for helping bring this magical evening to life. From the warm hospitality to the amazing food and seamless experience, it was the perfect way to mark such a meaningful moment in our journey.

![]()

The Road Ahead

We left Manly feeling re-energised, refocused, and deeply grateful. It’s easy to get caught up in the busyness of the everyday, but experiences like this retreat serve as a powerful reminder of who we are and what we’re building — together.

As we look ahead to the next five years, we’re more committed than ever to continuing to grow with intention, staying curious, and delivering meaningful results for our clients – and doing so in a way that keeps people and purpose at the centre of everything we do.

To everyone who made this retreat possible — thank you. And to the whole Sententia Consulting team, past and present — here’s to everything we’ve achieved so far, and to everything still to come. Cheers to the journey. 🥂

AUTHOR: DAVE HADDAD & SEAN MALONEY

Across the broader Australian Public Service (APS), there has been a marked increase in the attention and emphasis directed toward the concept of integrity.

This increased focus on integrity within the APS was initially driven by the Independent Review of the APS commissioned by the then Government in May 2018. The Review’s Final Report was delivered in 2019 and included a recommendation aimed at reinforcing APS institutional integrity to sustain the highest standards of ethics. The intention is to develop a pro-integrity culture within the APS, and work is still underway for this to be achieved. In October 2022, the Albanese Government announced its APS Reform agenda to further strengthen the APS. This agenda includes four priority areas, the first of which is an “APS that embodies integrity in everything it does”. Against this backdrop, there may have never been higher expectations placed upon public officials to conduct themselves with integrity.

To support public officials who are continuing to grapple with this increase in scrutiny and expectations, the APS has established principles and frameworks to direct and govern behaviour, that are aligned to legislation such as the Public Service Act 1999 and the Public Governance, Performance and Accountability Act 2013. These supports include defined whole-of-government standards such as the APS Values and APS Code of Conduct and are supplemented by agency specific corporate and HR policies.

But the success of these mechanisms is contingent upon, and may be limited by, their embrace and fulfillment by leaders. To effectively support the establishment of a pro-integrity culture and in order to encourage pro-integrity behaviour across the APS, it is integral to start at the top. The tone and values set by leadership, and the extent to which they are overtly espoused and lived up to, lays the foundation for a Pro-integrity culture and values-based behaviour.

In undertaking any assessment of whether leaders and leadership are positively impacting integrity culture, the following concepts are crucial to consider:

- The clarity of values-based communication from leaders.

- How staff perceive leadership’s expectations regarding integrity.

- The consistency of behaviour under pressure.

- How leaders handle their missteps.

The clarity of values-based communication from leaders.

As outlined earlier, tools and guidance have been developed with an intention to support consistent principles-based behaviour across the APS. However, as with many high-level policies intended to be broadly applicable, these constructs and concepts may be difficult for staff to translate and apply in their day-to-day roles. Many APS staff may in fact struggle to name all of the APS Values, or all elements of the APS Code of Conduct.

To bring integrity into practice, we must think at a more personal level. The behaviours and values of those we work amongst are easy to recognise and reflect. This is where leadership can start bringing conceptual integrity into practice. Convention says that culturally tone is set at the top, so it is imperative that leaders have a defined and, most importantly, well-communicated set of values.

So, while most leaders reflect on the question “What are my values?”, it is just as important to reflect on “Have I effectively communicated these values?”. In assessing the effectiveness of communication relating to values, the following should be considered:

- Has it been explicitly stated that something is right and/or if something is wrong?

- Is communication overt, public facing, and/or easily accessible?

- Is values/integrity related communication consistent in its messaging?

How staff perceive leadership’s expectations regarding integrity.

While the point above speaks to the efforts made by leaders to be effective in their communication, a key component of communication is in how it is received. The reception of this information, and how its messaging is perceived by staff, is the link between communication and improved behaviours. Determining whether this has occurred involves establishing if staff’s perception of what is right vs what is wrong, or what the important values to a team are, aligns to the expectations communicated by leadership.

Evaluation or reflection can help to identify, and subsequently rectify, any disconnects emerging in this space. This evaluation can be done by leaders or by anyone looking to review the impact of values and behaviours on integrity. It can be done through formal interactions, via structured data gathering activities or through informal conversations and observations. These activities should be looking to assess and consider the alignment of the values intended to be communicated by leadership and the perceptions of others.

Continual investment in understanding perceptions is important as it is these perceptions that are most likely to inform and drive behavioural change. This feedback should help to inform leaders of adjustments that made need to be made to their communications to support aligning perceptions with their intended outcomes.

The consistency of behaviour under pressure.

While developing a coherent set of values is integral in establishing a pro-integrity culture, consistency is how these become embedded in the mindset and behaviours of teams. Discussing and working in alignment with a strong set of values is far easier in a business-as-usual operating environment. Through consistent messaging and consistently living up to this messaging even in challenging moments, leaders can highlight the importance of the values they preach and set an example for their teams to reflect.

In reviewing the impact of leadership on driving improvements in integrity, this is the most important component to evaluate. When reviewing the behaviours and messaging of leadership, it may be complex to decipher intended messaging or how values are being communicated. It is much easier to assess if there is consistency in this messaging:

- Are the same things being prioritised/communicated?

- Is it easy to align values focused communication with current behaviours?

- Do decisions made under pressure align to the values espoused by leaders?

Through assessing the answers to the questions above, we can establish the degree to which integrity has been embedded in the consistent behaviours of our teams, and the effectiveness of leaders in supporting this outcome.

How leaders handle their missteps.

The final aspect of leadership to consider, is how to handle situations where a misstep has been made. When it comes to missteps that impact or impair perceptions relating to integrity, it is almost inevitable that the result is a loss of trust. This loss of trust may just be felt in those impacted, or it could occur more broadly amongst those we are charged with leading.

Trust is integral to a pro-integrity culture, so when the bonds of trust amongst a team or in a relationship have been impacted, an investment must be made to remediate this. This investment of time and effort should be underpinned by the following principles

- A commitment to the truth – when appropriate, efforts are made to be upfront and forthright regarding what has actually occurred.

- Transparency in accountability – leadership or others responsible for any mistakes are clear in taking accountability not only for their actions but for any and all consequences.

- A willingness to give – a proactive and genuine willingness to give advice, give time and give of yourself to those who have suffered for the lack of integrity in behaviours or actions.

A pro-integrity culture does not mean that no mistakes are made. However, it does mean that when they are made there are truths told, there is transparency in accountability, and there is an investment made to remediate any damaged trust. These principles, and the extent to which leaders have lived up to them, should be looked for when evaluating the impact of leadership in supporting the growth of integrity.

AUTHOR: SIMONE KNIGHT

World Quality Week – 11-15 November 2024

World Quality Week takes place every November. This global campaign raises awareness of the benefits of organisations taking a quality management approach to their operations.

This year’s theme is Quality: from compliance to performance. The timing couldn’t be better for those of us working with Federal Government. We’re now in Quarter 2, 2024-25, so we’ve had sufficient time settling into our Corporate Plans, we’ve finalised our Annual Reports and we are heading towards MYEFO. So how can our corporate documents lift and shift us to achieving high performance? Could a quality management approach be the solution?

Our Roles in Responding to Climate Change

One of our current challenges is how organisations are adapting to climate change. The Government’s push to net zero is also front of mind for many agencies. For those organisations certified or seeking certification under ISO 9001, there is a new requirement in the standard to consider the impacts of climate change as an internal or external factor. This amendment has been effective from 22 February 2024 and aims to integrate climate change considerations into management systems – not only quality management systems under ISO 9001, but also environmental management systems under ISO 14001 and work safety management systems under ISO 45001 (which are the three most widely recognised standards in the world).

Under ISO 9001 organisations are now required under clause 4.1 to assess the impact of climate change on operations to “understand the organisation and its context.” If climate change is identified as relevant to the quality system, it should be treated like other internal or external factors and included in the assessment of risks.

This imperative to address environmental concerns adds another layer of complexity to our operations and this of course, coincides with the Federal Government’s reporting requirements regarding climate change, including the Commonwealth Climate Disclosure requirement to publicly report exposure to climate risks and opportunities and actions to manage them. Under this policy, Commonwealth entities and Commonwealth companies must disclose climate-related information in their annual reports.

An additional amendment to ISO 9001 reinforces this through a new note to clause 4.2 that states “relevant interested parties can have requirements related to climate change.” While this note does not impose extra requirements, it clearly links the ISO 9001 standard to the requirements of interested parties, such as the Government, regarding climate change disclosures.

With that in mind, we should consider how quality management principles and methods allow organisations to respond, creating a culture of process improvement. Quality management can be associated with tools, processes, controls and governance. These elements are all-important, but an organisation’s culture is what will nurture innovation and continuous improvement to achieve high performance. Quality principles and methods not only ensure compliance but also foster learning and agility, to allow organisations to adapt to change more effectively and drive performance excellence.

Act Now

While some organisations will need to be more agile than others when it comes to adjusting for climate change impacts and fulfilling reporting requirements, there are some simple things you can do now to assess your organisation’s position:

Consider how climate change may affect your organisation

It’s important to consider both direct and indirect implications. Some direct implications include changes in weather patterns, rising water levels and government-imposed restrictions that may have an impact on the goods and services that are outputs of your organisation. You may need to adjust how you support human resources, change your physical infrastructure, and start capturing data about climate change related performance.

Indirect consequences may include the introduction of new technologies, shifts in the behaviours of the public and the potential for business disruption as a result of changing weather patterns. You may also experience changes in your supply chain and consumer behaviours.

Assess your risks and opportunities

Remember that not all impacts of climate change need to be negative. As we said above, a quality approach encourages innovation, and climate change may well present the catalyst for designing new practices that create efficiencies and take advantage of new technologies. It may also be an opportunity for a reputational boost for your organisation. Over three quarters of Australians[1] (78%) are worried about climate change and extreme weather events in Australia. Climate action by your organisation may have a positive impact on the way the public responds to your organisation.

Develop an action plan

You may need to update your policies and procedures (including to cover the requirements of clause 4.1), develop and implement training for personnel, incorporate climate change into the governance of decision-making, put in place practices to enable the capture of climate change data, and implement reporting procedures.

If your organisation is ISO certified, auditors may seek evidence that you have considered the issue of climate change. To provide this evidence, we recommend you demonstrate climate change consideration in your organisation’s documentation including by documenting the actions you are taking (your action plan), be transparent with internal and where appropriate, external, audiences about those action plans and ensure they are maintained and kept up to date to reflect the current state of your activities.

Recognise that climate change will involve continuous improvement

Risk assessment and actions relating to climate change impacts will not be a once-off activity. You may need to develop strategies and build performance targets that are reflective of an increasing maturity as your organisation learns to adapt to climate change.

Drive performance

Here are some top tips from the Chartered Quality Institute[2] to harness a quality management approach to drive performance:

- Embrace innovation: Don’t just meet compliance standards; leverage quality management to drive innovation and stay ahead of the curve.

- Manage risks proactively: Identify and mitigate risks associated with digital transformation and other strategic initiatives to ensure long-term success.

- Focus on sustainability: Integrate sustainability into your quality management practices creating products and services that are environmentally and socially responsible.

- Promote a learning culture: Encourage continuous learning and improvement within your organisation to adapt to changing market conditions and customer needs.

What’s Coming Next in the World of Quality Management?

Some emerging quality management issues which may well form part of the next amendment to the ISO standard (expected for 2026 implementation) include:

- A change in the focus on customer satisfaction to a broader concept of ‘customer experience’;

- Integrity and ethics in decision-making;

- Increasing customer expectations of organisations to deliver sustainable innovation where promoting good operational governance, assurance and improvement will support delivery safely and confidently; and

- AI, digitalisation and automated decision-making, which present both opportunities for performance enhancement and risks for many organisations

Why Choose Sententia?

At Sententia Consulting, we believe that quality management provides organisations with a framework that is valuable in supporting improvements in operations to achieve high performance.

We understand that not all organisations are pursuing ISO certification, and we take a pragmatic approach to support organisations to implement quality practices that are fit for purpose. We can help you stay compliance and future-ready with our expertise.

If you are interested in learning more about how Sententia can help you, please see www.sententiaconsulting.com.au or email us at sententia@sentcon.com.au.

[1] www.climatecouncil.org.au from a recent survey conducted in March 2024.

[2] https://www.quality.org/WQW24

AUTHOR: BRIONI BALE

The Australian public service supports Government to develop, implement and update Australian policy which can have population-wide impacts. Project managing policy change can be a challenge due to the complexity, tight delivery timeframes, inclusion of many stakeholders and the high sensitivity to risk, uncertainty and changing political environments. Outputs stemming from policy change are often less specific and are more focused on longer-term outcomes. How policy outcomes will be achieved can be unclear and can continue to change as the policy is developed, negotiated and agreed to by Government. The implementation of policy is typically more contentious or polarising than other types of change.

Good project management is essential to ensure successful delivery of policy outcomes, which can be significant, challenging to deliver and may require a different project management approach, when compared to other types of large-scale projects. This article explores how policy project management differs and provides techniques that can be used to improve successful delivery of policy in Australia.

Why is policy project management different?

- When compared to other types of projects, policy projects typically attract broader stakeholder interest (Ministers, their staff, government agencies, industry, industry bodies, consumers and, the public more generally) due to their potential for broad population impact. Other project types have more limited and specific stakeholder interest. There may be a large number of stakeholders, but the variety is generally less.

- Communication is important on all types of projects, but effective communication is essential in policy projects to gain support from stakeholders, influence public opinion, and ensure successful implementation. Communication in other types of projects tends to be more focused on internal updates, user engagement and marketing type activities.

- Developing policy involves extensive research and analysis (data collection, impact assessments and evaluation of pre-existing policies). Evidence-based decision-making is crucial to show the need for the policy, as well as supporting the development of sound policy. Research and analysis may also be important in other types of projects but it’s generally market research, technical feasibility, or user experience.

- Policy projects must consider legal and regulatory frameworks, compliance issues, and the potential for legislative changes. Public consultations are often necessary and there is generally always a need for some sort of legal advice. Where legislation is part of the policy, Parliamentary processes must be followed, which can take considerable time. Non-policy projects may need to consider regulations and compliance but typically not to the same extent.

- Implementation often involves multiple phases and can include pilot programs to better understand impacts. Specific evaluation points can be established to measure the effectiveness of the policy to allow for adjustments if needed. Other project types focus more on project roll-out, user adoption and iterative improvements over time based on feedback.

- Policy projects are generally funded by public money or grants, which comes with an increased need for transparent reporting and accountability to ensure value for money. Formal policy authority from Government is required. Other project types are funded by private investments, internal budgets, or revenue, with different accountability mechanisms.

Understanding the differences between policy and other types of large-scale projects is crucial to establish fit for purpose project management, to ensure policy-specific challenges and requirements are addressed throughout the project delivery.

The challenges and complexities of policy projects

There are many challenges and complexities associated with the development and implementation of policy.

- Policy projects often have interdisciplinary needs, requiring expertise from multiple disciplines i.e. economics, legal, clinical, sociological, technology. Different disciplines and the greater numbers of stakeholders involved in policy development create different project outcome expectations.

- It can be difficult to define the scope of a policy project due to ongoing changes as the policy intent is established and the realities of implementation are realised. A further contributor to scoping difficulties is the funding process, which can contribute to outcome expectation inconsistencies when requested and allocated funding are not the same, limiting or changing achievable outcomes.

- Uncertainty i.e. economic fluctuations, changes in political environment, natural disasters can impact policy outcomes and effectiveness. It can also complicate the translation of policy into action. Implementation complications could include logistical planning, management, monitoring, resistance, lack of capacity, or unforeseen changes.

- Gathering, analysing, and interpreting large volumes of data, is often necessary to inform policy decisions, which can be resource-intensive, time consuming and technically challenging. Privacy requirements always must be taken into consideration. Balancing competing ethical considerations, such as equity, fairness, and the public good, can add another layer of complexity to policy design and implementation issues.

- Policy benefits are often intangible and can be hard to identify and baseline in a manner that can be effectively measured. Often, benefit realisation cannot occur for considerable time after the completion of the project making evaluation difficult.

- Project management in policy environments is often undertaken by teams with limited dedicated project management capability and capacity which can impact project delivery and implementation success.

How to improve policy project delivery efficiency and effectiveness

With an understanding of how a policy project differs to other project types, and recognition of the complexities and challenges associated with policy project management, there are steps that can be taken to increase policy delivery success.

- There is a need for a deep understanding of the policy intent and any changes made to the policy through its development and implementation. Establishing artefacts and processes to underpin the project is important, but understanding the policy itself will improve delivery and outcomes.

- Taking a flexible project management approach, with consideration of the public sector team’s capability, maturity, capacity, risk appetite and leadership expectations can increase buy-in and improve internal capability.

- Building trusting relationships with public sector team members and leadership. Policy-specific subject matter expertise is generally found in operational team members. It is just as important to have good relationships with project team members as it is with leadership. Being in the trenches with the team is one of the best ways to build trust.

- Make exceptions when they are needed. Hard and fast rules sometimes do not work, and they do not win you friends or influence people. Sometimes, it is appropriate to make an exception where it supports the team.

- There is a need for fluid contingency planning, done in a flexible way, which considers the complexities of the project. There are often too many moving parts to set up one or two contingency plans and stick with them.

Building true partnerships with policy delivery teams leads to more successful delivery outcomes. The use of our project management capability alongside the policy subject matter expertise in the public sector leads to improved policy delivery and outcomes.

AUTHOR: CONOR WYNN, PHD

The following article is republished from Sein with permission.

We like to think that big policy decisions are made thoughtfully, informed by data, with careful consideration of the facts and after a deliberate weighing of the options. Not so it seems.

It turns out that the political elite use ‘rules of thumb,’ also known as heuristics, to make the big decisions1. So who are these people, why do they decide that way, and is it OK that they do so?

The elite is a small group of individuals who occupy prominent positions in society, and who have preferential access to resources and an outsized impact on events. They tend to recognise one another, act and think alike. The political elite is a subset, comprised of politicians, senior bureaucrats, and advisers. Politicians in power face a 24/7 news cycle, deal with complex problems and divergent opinions. And though this is what they signed up for, it can lead to the political elite relying on heuristics to cope.

Which heuristics do the political elite use and why?

The literature shows that the political elite are prone to use heuristics such as, being more sensitive to losses than gains, also known as prospect theory, status quo bias, overconfidence – leading to poor decision-making, which when combined with escalation of commitment could help explain why once having made a poor decision, the elite are also prone to doubling down on previous commitments and stereotyping2 to name a few.

There are seven factors that influence the political elite in using heuristics:

- Experience: the greater the experience the more effective use of heuristics3.

- Context: Greater experience in similar contexts appears to allow the more experienced to get to an acceptable outcome more quickly than those with less experience4.

- Complexity: More complex issues are associated with the greater use of heuristics5.

- Urgency: The greater the urgency the more likely the use of heuristics6.

- Self-interest: For example, gaining or remaining in office.

- Ideology: Political ideology such as conservatism or socialism can be used as a heuristic.

- Emotion: For example, the British prime minister Herbert Asquith’s decision to enter World War One was thought to have been influenced by anger and fear7.

The issue is though—is that OK?

Is it good enough, for example, that a decision to go to war is influenced by heuristics, or should we expect a more thoughtful approach before placing troops in harm’s way?

Is it OK to use heuristics for political decision-making?

There are two leading schools of thought around the use of heuristics. The heuristics and bias (H&B) school lead by the Nobel laurate Daniel Kahneman, and the fast and frugal (F&F) school led by Gerd Gigerenzer.

The H&B school argues that there are two styles of decision-making—either quick or deliberate8, however there are a few caveats. These decision-making styles could be thought of as being at opposite ends of a spectrum, and by implication, a blend of these two decision-making styles is likely, as is a sequencing of different decision-making styles, e.g. using heuristics to narrow down the range of choices, then a deliberate approach to choosing between them. But when it comes to political decision-making Kahneman argues that heuristics should not be used9, whereas Gigerenzer allows for their use in political decision-making10. So, which school is right? Unfortunately, it’s not that straightforward.

The problem with political decision-making is that often the answer to a question is unknown in advance, because the problems are complex. The lack of a “correct” answer makes testing alternatives impossible. To make matters worse, decision-making by the political elite make can be motivated by their desire to stay in office11. And so, it’s not possible to test motivated decision-making in an objective sense, because it is subjective—by definition.

Notwithstanding the impossibility of a binary solution to the debate about the use of heuristics in political decision-making, we wanted to learn more. So, we managed to secure rare access to 21 senior ex state politicians, their advisers, and senior former bureaucrats discussing an innovative but politically difficult transport pricing policy proposal.

Transport pricing reform

Road congestion in large cities is a significant issue in Australia. Charges for road use are levied upfront (e.g. vehicle registration tax) and do not reflect actual road usage. An alternate approach to transport network pricing (TNP) would be a user pay system where those who travel during peak times, for greater distances or into highly congested zones would pay more than those who didn’t. And so, there was political risk.

The discussion forum

There were 21 participants, six of whom were current or former senior politicians (from both major political parties), seven current or former senior bureaucrats (i.e. heads of departments), and eight current or former political advisers. Participants were drawn from the two major parties, for balance. And as the participants were no longer in positions of executive power, we hoped to minimise the risk of presentation management overlaying the decision-making process. An extensive briefing document was provided to all participants in advance, including a detailed business case, economic modelling, pricing recommendations, traffic projections and demographic analysis.

What we found — whether to engage and how to engage

We found that the political elite used heuristics in two ways.

First, to decide whether to engage with an issue, using the “wait-and-see” heuristic. And second—having decided whether to engage—how to engage, using political empathy to guide their actions on TNP.

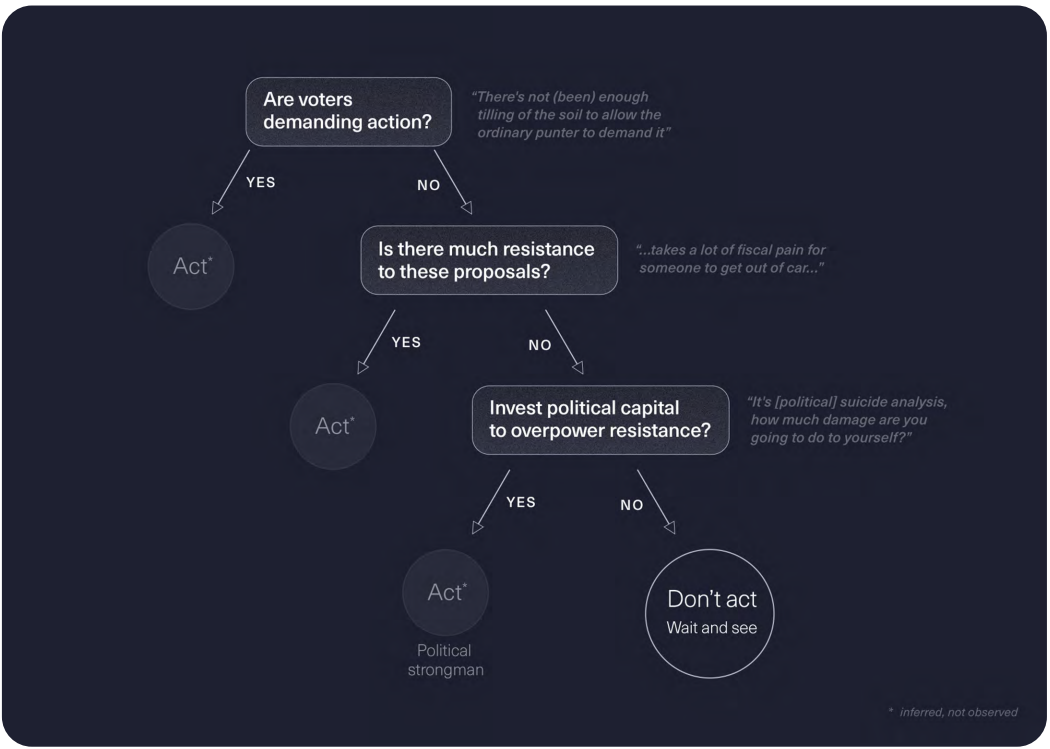

Whether to engage — the “wait and see” heuristic

The primary concern of the elite we observed was not judging the TNP in isolation on its merits, rather whether they ought to engage with the TNP at all. In other words, they didn’t act as judges, considering the facts of each case brought before them. Instead, they behaved like investors, deciding which stock to invest in from a broad market.

So, the first question they asked was – are voters demanding action? They sensed that though there was dissatisfaction about traffic congestion, community sentiment hadn’t crystallised to the point where action was being demanded. The issue wasn’t making headlines, and so, the answer to the first question was “no”, the issue wasn’t urgent and didn’t demand action. This led to the second question; if this issues wasn’t urgent, yet they pressed ahead with implementing the TNP regardless – would there be much resistance?

In a telling comment, a senior politician summed up the situation, based on his experience of trying to change car usage behaviour through pricing signals alone:

“Pricing hasn’t worked. [It] takes a lot of fiscal pain for someone to get out of a car.”

Politicians representing outer suburbs feared community pushback from increased costs which cast a shadow of self-interest over their decision-making.

So, the calculation was – “yes”, there was a risk of strong resistance to those proposals from segments of the community. At this point they thought – the matter isn’t urgent, there’s likely to be pushback and so they asked the third key question – if we impose this policy against the wishes of the electorate…

“are we prepared to spend the political capital needed to overpower that resistance”

This strategy, characterised as the “political strong man” approach had been used in New York, London, and Singapore for example. A former adviser summarised the group’s dilemma at this point in the decision tree.

“It’s [political] suicide analysis, how much damage are you going to do to yourself?”

A former senior bureaucrat summed up the three step decision tree with a pointed question:

“Does any politician think that the big problem is congestion and that the answer is pricing?”

The matter was decided quickly with the answer to this question by a senior former politician:

“No. Not yet.”

How to engage — political empathy

To identify the heuristics voters might use to judge the proposal, the political elite used political empathy – putting themselves in voters’ shoes to identify which heuristics voters would use when judging a policy.

To help them with political empathy they used:

- Stereotyping – the forum established “Cranbourne man” as the typical suburban voter

who is independent, easily upset and whose key concern is access to roads. - Trust – participant’s view was that the greater the trust, the more likely voters would be to support an innovative policy. So, if the government could demonstrate a track record of successful delivery, voters would be more likely to trust them with large issues such as the TNP.

- Incrementalism – the forum thought that if the public became used to new pricing arrangements on electric vehicles, they would be more amenable to the TNP.

- The decoy effect – when an obviously less attractive option is included in a set of alternatives

with the aim of influencing choice towards a recommended option.

And so, the complex issue of whether to engage with the TNP was decided. It was a decision not to engage, or a decision to make no decision. A previously identified12 but not observed heuristic of “wait-and-see” was used to decide the fate of an innovative policy proposal.

So what?

While we identified seven factors that influence the use of heuristics by the political elite, we saw five in play at our forum – experience, context, issue complexity, and urgency. Though our forum members were highly experienced, they were not experts in transport pricing policy and so context was key. The matter was highly complex, and as there was no pressing need to decide, urgency was low. The combination of those factors influenced decision-making style, and caused them to use both styles of thinking, not either.

The politicians we observed made a decision about a decision, which could be considered deliberate decision-making based on elaborate thought, so supporting the F&F school. However, in arriving at that decision they did not consider the details of the extensive briefing materials, rather they used a three-step process to reach an acceptable answer quickly – the hallmark of heuristic decision-making, preferring to “wait-and-see”.

While it looks like an important question – is it OK for heuristics to be used for political decision-making, it turns out that this isn’t a good question after all. This forum showed that both styles of decision-making can be appropriate, rather than one or the other. And while most studies of political decision-making focus on decision-making, few address political non-decision-making. For the first time to our knowledge, we found evidence of the use of heuristics for avoiding a decision, and the shaping of public policy by inaction.

How to avoid indecision or “irrational” decisions from the political elite

When dealing with political elite, there’s a real risk that there either won’t be a decision, or one that “doesn’t make sense”, so what can be done to avoid those poor outcomes?

- Try to re-engage the decision makers on the detail, so forcing deliberate thinking, but there are problems with this approach. The likelihood of success is low – we know the political elite like to use heuristics13. And secondly, as there are some situations where heuristics are preferable to elaborate thinking14, so it’s possible that for instance now is not the right time for the proposal.

- Encourage decision makers to become aware of their biases possibly through leadership development programs. Once again there are problems with this approach. Telling someone important that their decision-making is biased, and they should re-train could be career limiting. And including de-bias training in general leadership development training programs, so that when leaders do emerge into senior roles they rely less on heuristics is a very long-term play. Worse still, there’s evidence that such training programs are either useless15, or can backfire16.

- Use the decoy heuristic by adding an obviously inferior alternative to the one you prefer. While this might have the desired effect it’s ethically questionable. At minimum you could be accused of libertarian paternalism, or at worst manipulative.

- Take a portfolio view of all your policy proposals and put them to the “wait and see” heuristic test to spot which ones might struggle to get leadership engagement. This has legs. It recognises that the political elite use heuristics rather than pushes back against it, and so is a pragmatic choice. It provides feedback on which of your proposals is likely to be successful and which could end up in deep freeze. Armed with that information, you could re-allocate your resources to those proposals with greater chances of success, becoming more effective in the process. And, in looking at those proposals that didn’t pass the “wait-and see” test, you might discover which conditions need to change or be changed for them to pass the test.

In summary, there’s evidence that heuristics have their place in decision-making, and that a blend of deliberate thinking and heuristics is effective.

But the issue is not the theoretical one of whether important people ought not use heuristics, it’s the pragmatic one of how to cope with the fact that they do. The “wait-and-see” heuristic is alive and well among the political elite, understanding how to deal with it is key.

- Stolwijk, S., & Vis, B. (2020). Politicians, the Representativeness Heuristic and Decision-Making Biases. Political Behavior. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11109-020-09594-6

- Bordalo, P., Coffman, K., Gennaioli, N., & Shleifer, A. (2016). Stereotypes. Quarterly Journal of Economics, 131(4), 1753-1794. https://doi.org/10.1093/qje/qjw029

- Hafner-Burton, E. M., Hughes, D. A., & Victor, D. G. (2013). The Cognitive Revolution and the Political Psychology of Elite Decision Making. Perspectives on Politics, 11(2), 368-386. https://doi.org/10.1017/s1537592713001084

- Klein, G. (2008). Naturalistic decision making. Human Factors, 50(3), 456-460.

- MacGillivray, B. H. (2014). Fast and frugal crisis management: An analysis of rule-based judgment and choice during water contamination events. Journal of Business Research, 67(8), 1717-1724. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jbusres.2014.02.018

- Chaiken, S., & Trope, Y. (1999). Dual-process theories in social psychology. Guilford Press.

- Young, J. W. (2018). Emotions and the British Government’s Decision for War in 1914. Diplomacy & Statecraft, 29(4), 543-564. https://doi.org/10.1080/09592296.2018.1528778

- Kahneman, D. (2011). Thinking, fast and slow. Macmillan.

- Kahneman, D., & Klein, G. (2009). Conditions for intuitive expertise: a failure to disagree. American Psychologist, 64(6), 515.

- Gigerenzer, G. (2008). Why heuristics work. Perspectives on Psychological Science, 3(1), 20-29.

- Bowler, S., Donovan, T., & Karp, J. A. (2006). Why politicians like electoral institutions: Self- interest, values, or ideology? The Journal of Politics, 68(2), 434-446.

- Walgrave, S., & Dejaeghere, Y. (2017). Surviving information overload: How elite politicians select information. Governance, 30(2), 229-244.

- Stolwijk, S., & Vis, B. (2020). Politicians, the Representativeness Heuristic and Decision-Making Biases. Political Behavior. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11109-020-09594-6

- Gigerenzer, G., & Goldstein, D. G. (2011). The recognition heuristic: A decade of research. Judgment and Decision Making, 6(1), 100-121.

- Noon, M. (2018). Pointless diversity training: Unconscious bias, new racism and agency. Work, employment and society, 32(1), 198-209.

- Atewologun, D., Cornish, T., & Tresh, F. (2018). Unconscious bias training: An assessment of the evidence for effectiveness. Equality and Human Rights Commission Research Report Series.

This article is based on an article published in the Australian Journal of Public Administration, the peer reviewed journal of the Institute of Public Administration Australia.

AUTHOR: JOSIE LOPEZ

With the increasing focus on environmental, social and governance (ESG) issues, mandatory climate disclosure reporting is being introduced around the world to provide information on an organisation’s progress towards their ESG goals. To demonstrate their commitment to acting on climate change in their own operations, the Commonwealth Government has introduced Climate Disclosure Reporting for Commonwealth entities and Commonwealth companies.

Like the introduction of Performance Statements into Commonwealth Government reporting, the introduction of Climate Disclosure Reporting will be applied in a phased approach to allow entities to develop their maturity over time. However, do not let this phased approach lull you into a sense of false security, for entities and Accountable Authorities to properly discharge their responsibilities under Climate Disclosure Reporting entities must invest in the relevant resources and take the time to develop and implement the appropriate infrastructure to support this reporting.

What is expected of entities under climate disclosure reporting?

There will be two streams of disclosure requirements for Commonwealth entities and

Commonwealth companies:

- Stream 1 – for Commonwealth companies equivalent in size or greater than ASX 300 and Commonwealth companies equivalent in size to large proprietary companies with material climate risks. Climate-related financial disclosures for this stream will be led by the Department of Treasury.

- Stream 2 – all other Commonwealth entities and Commonwealth companies. Climate-related disclosures for this stream will be led by the Department of Finance.

The Department of Finance expect to finalise the Commonwealth Climate Disclosure requirements for Stream 2 in mid-2024. Therefore at the time this paper was written, only the requirements for the Pilot had been released. However, the Department of Finance notes that the requirements will align with climate disclosure standards set internationally by the International Sustainability Standards Board (ISSB), nationally by the Australian Accounting Standards Board (AASB), and be tailored for government and the regulatory and policy environments under which they operate (e.g. APS Net Zero by 2030).

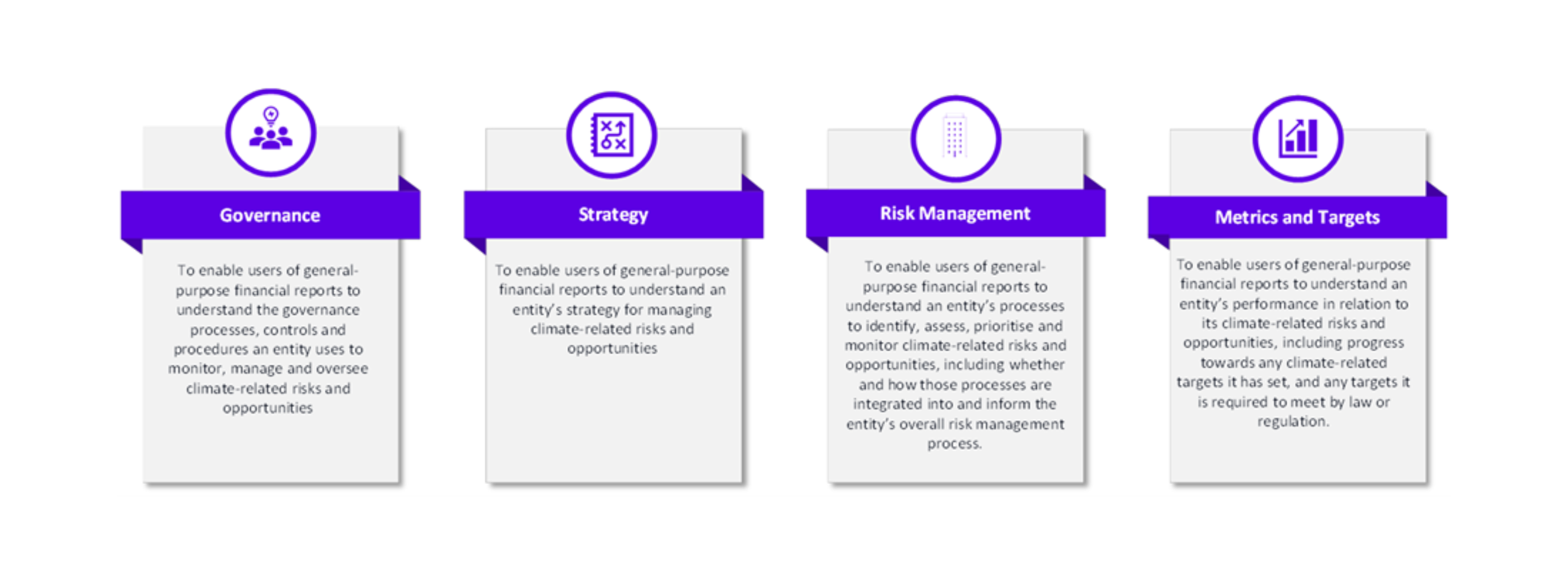

The pillars of Climate Disclosure reporting within International Financial Reporting Standards Sustainability Standard S2 Climate-related Disclosures that will be featured within the Department of Finance’s disclosure requirements include:

It is noted that the pillar of ‘Strategy’ is not included in the Pilot for Departments of State, however this pillar will be included in the required disclosures by the Department of Finance from 2024-25.

How do I prepare for Climate Disclosure Reporting?

Similar to the introduction of Performance Statements and the new Australian Accounting Standards for Revenue and Leases, entities that are not aware of their requirements and adequately prepare for climate disclosure reporting will get caught out in the first year of reporting.

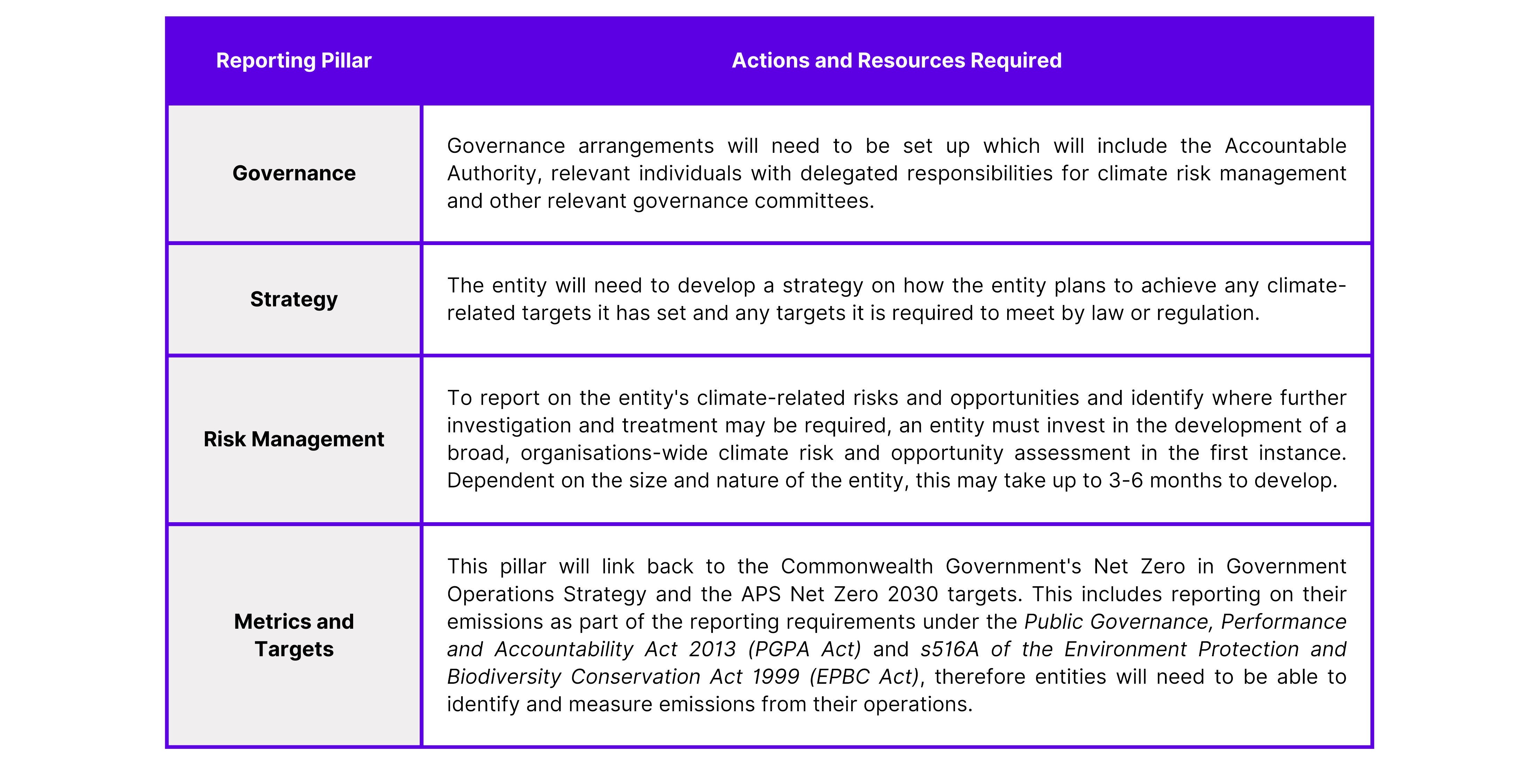

For an entity, and therefore an Accountable Authority, to properly discharge their responsibilities under Climate Disclosure Reporting, an entity must take the time to ensure that they have the right resources and infrastructure in place. To report on the four pillars, this will include:

Although capacity building support is being provided to Commonwealth entities and Commonwealth companies to help them meet their climate disclosure obligations, entities need to ensure that they have dedicated resources with the capability and experience to be able to properly report on their climate disclosure requirements. In addition, employee engagement and staff led initiatives will be important to achieving net zero grassroots climate action and broader sustainability. Dependent on the size and nature of the entity, to ensure that there is the appropriate infrastructure, frameworks and level of executive involvement, this may require the establishment of a Chief Sustainability Officer, a Climate Sustainability and Assessment Team, a Risk Management Team and an Environmental Contact Officer Network (a volunteer-run network of staff committed to reducing the environmental footprint of the entity’s operations).

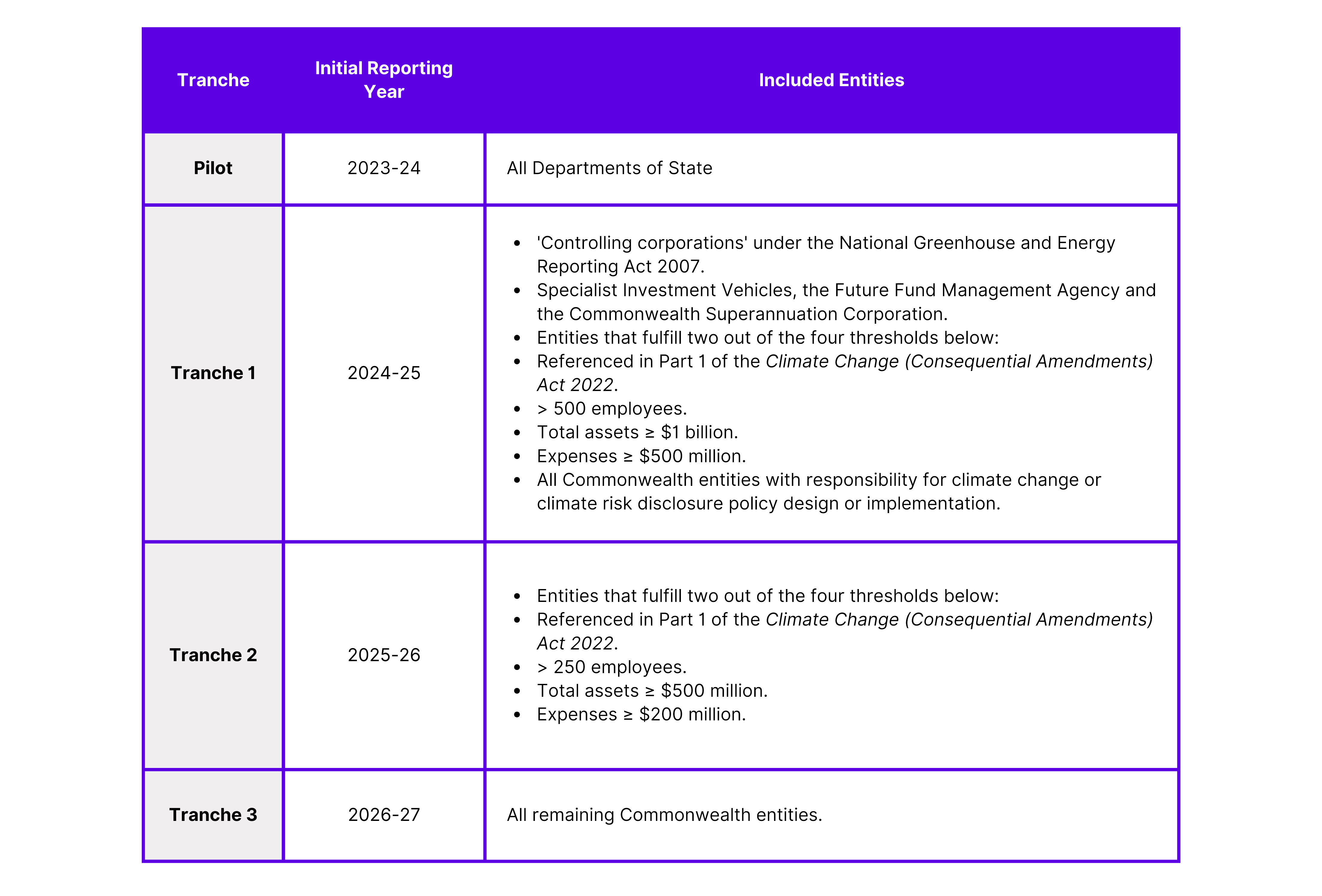

When do I have to report?

The following table details the tranche and initial year of reporting for all Commonwealth entities under Stream 2:

Will my sustainability report be audited?

The Department of Finance will be developing a verification and assurance regime in consultation with the Australian National Audit Office (ANAO) to be applied to Stream 2 entities. Like the initial Performance Statement reviews conducted by the ANAO, the focus of the regime will be on improving the quality of climate disclosures. We believe that over the years as the maturity of climate disclosure reporting increases within the Commonwealth, like the Performance Statements there may be a move to mandatory audits which will include the issue of an audit opinion in the form of positive assurance over compliance with the Commonwealth climate disclosure reporting requirements. With this in mind, entities should develop their climate disclosure reporting frameworks to ensure that there is rigor and robustness within processes to identify and capture applicable data, and ensure that the governance around this function supports the complete and accurate reporting of the climate disclosure requirements of the entity. This will also provide the Accountable Authority with comfort over what the entity is reporting as well as their progress in line with the Commonwealth Government’s commitment to Net Zero in Government operations.

Should Internal Audit get involved?

Internal Audit should play a significant part in an entity’s preparedness for Climate Disclosure Reporting, and now is the perfect time for Internal Audit to get involved! Internal Audit should be making contact with the line areas responsible for Climate Disclosure Reporting and integrating into an assurance program over the four pillars of reporting. Real time assurance as the entity progresses around the framework for Climate Disclosure Reporting, as well as assurance over results to be reported, will provide relevant governance committees and the Accountable Authority comfort in what the entity is reporting to both government and the public.

Conversely, line areas responsible for Climate Disclosure Reporting should be reaching out to Internal Audit to provide them assurance around the rigor and robustness of their processes for Climate Disclosure Reporting.

AUTHOR: JO CARROLL

In both the Public and Private sectors, it is important that individuals, programs and

organisations are held to account to deliver performance outcomes. Within the

private sector, profitability is the measure most often used, however we are seeing

an evolution with the increased focus and priority given to Environmental, Social

and Governance (ESG) reporting. Within Government the Annual Performance

Statements is the way in which performance is measured and reported,

implemented with the introduction of the Public Governance, Performance and

Accountability Act 2013 (PGPA Act) which established the system through which

accountability for public resources is to be governed.

In the public sector Annual Performance Statements is a regular audit topic on

Internal Audit Work Programs. As the Australian National Audit Office (ANAO)

continues to expand its external audit program, internal audit functions can help

their agencies to prepare for external audit, and address findings and

recommendations from ANAO work program.

Audits of Annual Performance Statements started to find their way onto our work

programs around 2019 when the ANAO commenced its pilot program. These audits

were focussed on the accuracy of the data presented in the statements. As time

progresses, we are seeing more value being added by audits that assess the

measures themselves and flesh out grey areas beyond prescriptive rules. Providing

assurance that agencies have coverage of material or key activities, an appropriate

balance of efficiency, outcome and output measures and a rigorous approach to