We recognise the continuous and deep connection to Country, of Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander peoples as the first peoples of this nation. In this way we respectfully acknowledge the Traditional Custodians of this land, sea, the waters and sky. We pay tribute to the Elders past and present as we also respect the collective ancestry that has brought us all here today.

AUTHOR: JAMES CHAPMAN

The Promise vs. the Reality

AI has been widely identified as the next great engine of productivity growth; often compared to the transformative impacts of electricity or the internet. Yet despite billions of dollars invested, the productivity boost so far has been modest. Real-world gains remain incremental, narrow in scope, or uneven across sectors[1]. For many organisations, expectations have outpaced actual outcomes.

Why This Shouldn’t Surprise Us

This gap between hype and reality should not surprise us. We are living through a period of structural uncertainty; caught between the established environment and an emerging one still taking shape. This uncertainty is reflected in organisational investment behaviour. In November 2024 a Detons’ survey identified 69% of business leaders were pausing capital expenditure[2]. Similarly in July, The Cube Research identified that 87% of businesses were taking a ‘cautious approach’ to tech spending[3]. In both cases, AI uncertainty was identified as a key contributor to this decision.

This makes sense when you imagine uncertainty in the context of a new project. Imagine you are responsible for:

- Launching a new public-facing ICT service – would you design your customer support entirely through a chatbot, knowing public trust in AI is still forming?

- Delivering a new case management system – do you integrate a generative AI search capability now, or wait until regulations clarify how client data can be processed?

- Leading a major workforce redesign – do you restructure roles now based on current automation capabilities, or wait, knowing AI may soon take on tasks we still consider uniquely human?

Each of these scenarios highlights the uncomfortable but inevitable reality of transition: we are building the plane while flying it.

The Role of Project Professionals

While there are significant ethical, regulatory, and technical challenges associated with AI adoption, the focus here is narrower and more practical: the role of project professionals.

We are not passive bystanders. We have a responsibility to optimise our approaches, sharpen our processes, and support our stakeholders so that projects can navigate this uncertain terrain more effectively.

If AI is to deliver on its promise, it will not be solely because of algorithms or cloud infrastructure; it will be because project professionals made it possible to align people, process, and technology during a volatile period.

Principles for Managing the Transition

I believe there are four key principles that can help project professionals manage uncertainty:

- Clarity of strategic planning – In a volatile environment, clearly articulating project goals and objectives is essential. Defining, documenting, and securing agreement on these goals ensures your project can navigate a radically changing landscape. Equally important is documenting assumptions — they provide a vital reference point when assessing whether the project is drifting off course.

- Flexibility in execution – Embracing agile delivery methods provides the adaptability needed in times of change. I often use a Horizon delivery approach: setting regular planning windows to reassess progress and define the next tranche of outcomes, followed by focused delivery phases. This approach provides enough certainty for teams to deliver priority work while avoiding over-planning into an uncertain future.

- Flexibility in project governance – Rigid governance can block timely decision-making. In volatile environments, this undermines a project’s ability to deliver value. Instead, governance should empower teams with the autonomy to make tactical decisions while maintaining alignment with strategic goals. Real-time automated dashboards should replace static status reports, providing decision-makers with up-to-date visibility and reducing response lag.

- Embrace graceful project failure – Even with the best planning and flexibility, project delivery remains risky. We need to foster an environment where failure is not stigmatised but managed. A graceful failure closes cleanly, recycles resources, and preserves trust. A catastrophic one bleeds money, morale, and credibility. Encouraging frank advice and trusting leadership to act decisively allows organisations to recover quickly and redirect investment to more viable initiatives.

AI may yet deliver a productivity revolution, but for now the returns are uneven and the environment unsettled. In this transitional era, project professionals are not just implementers — we are stewards of resilience and enablers of progress. By applying disciplined yet flexible practices, project professionals can ensure that AI’s eventual productivity revolution is realised responsibly, efficiently, and with purpose.

[1] https://opendatascience.com/most-enterprise-ai-investments-deliver-no-return-mit-report-finds/

[2] https://www.dentons.com/en/about-dentons/news-events-and-awards/news/2024/november/ai-investment-trapped-by-regulatory-uncertainty

[3] https://thecuberesearch.com/283-breaking-analysis-tech-spending-remains-persistently-uncertain

AUTHOR: SAHANA SREENATHA

Government delivery has never been more complex. Policy priorities shift throughout project or program delivery, budgets are tightened, emerging technologies cause disruption, and teams restructure at a fast pace. Uncertainty is not going away. The challenge for agencies is not how to eliminate it, but how to build resilience so that projects, programs, and people can thrive in spite of it.

For many, the Project Management Office (PMO) has been seen as an administrative layer, a compliance checkpoint, or a collector of status reports. In practice, when resourced and empowered, it becomes something much more valuable. At its best, it is the Peace of Mind Office, providing clarity, confidence, and continuity in an unpredictable environment.

Rethinking the Value of PMOs

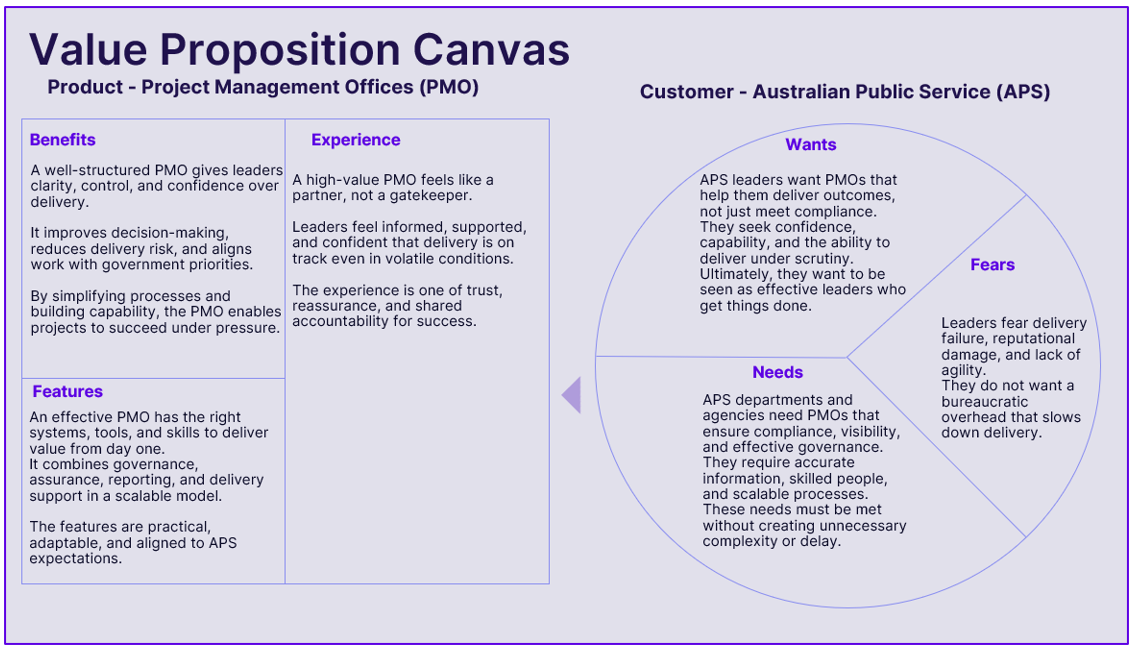

It is easy to define a PMO by its functions such as governance, reporting, risk management, and assurance. But a more useful perspective is to consider it through a Value Proposition Lens.

When the PMO is treated as a product and the public sector as its customer, its role becomes clearer. As per the Value Proposition Canvas diagram below; the product side encompasses the benefits it delivers, the experience it creates, and the features it provides. The customer side reflects the aspirations of leaders, the needs of various departments and agencies, and the fears that influence decision-making.

This framing highlights the difference between a PMO that enables resilience and one that simply ticks compliance boxes. Leaders want impact and credibility, they need decision-ready information and trusted frameworks, and they fear failure, wasted resources, and reputational damage. A well-positioned PMO addresses these directly, while a poorly supported one risks amplifying them.

Why Experience and Capability Matter

The value of a PMO is seen not only in what it delivers, but in how it shapes the experience of delivery. Organisations that position PMOs as trusted partners create cultures of openness, where project managers feel safe to escalate risks early and leaders feel supported rather than scrutinised. This shift from defensiveness to collaboration is where resilience begins to take hold.

Capability is the defining factor. Skilled staff transform the PMO from a reporting channel into a trusted advisor. A clear mandate allows it to influence decisions rather than simply reflect them. When these conditions are in place, the PMO provides foresight when priorities change, reduces risk under scrutiny, and enables leaders to make confident and credible choices.

Adaptability also matters. Delivery approaches across government have shifted significantly, with many Information Technology based projects moving away from traditional Waterfall methods towards Agile or hybrid models. These shifts offer opportunities for greater flexibility and responsiveness, but they also create new challenges, including increased documentation, additional approvals, and the need to balance agility with assurance. PMOs play a critical role in navigating this transition. By embedding governance frameworks that are scalable, proportionate, and responsive to context, they allow agencies to capture the benefits of Agile without losing the discipline required for accountability and oversight.

Examples from recent government initiatives that have demonstrated this outcome:

- Where PMOs were empowered to align frameworks with workflow systems, administrative burden was reduced and compliance strengthened.

- Where they were deliberately staffed and resourced, they helped the department/agency adapt quickly to shifting priorities, providing both stability and foresight.

These are practical outcomes that reflect the difference a strong PMO can make.

Meeting the Needs of the Public Sector

Public sector leaders want PMOs that are enablers of outcomes, not blockers of progress. They need compliance and governance that do not drown delivery in red tape. They are concerned about reputational damage from failed projects, the strain of under-resourced PMOs, and delays when timely advice is needed.

Meeting these aspirations, needs, and concerns requires more than just focusing on the delivery processes. It requires PMOs that build strong relationships, tailor frameworks to project context, and provide reliable information at the right time. Above all, it requires capability. Without skilled staff, the PMO charter risks being watered down, reducing its ability to influence and increasing the risks it is meant to manage.

The Future of the PMO

PMOs tend to operate in a landscape defined by uncertainty, shifting priorities, and an increasing demand to do more with less. Organisations are moving away from rigid Waterfall delivery models toward Agile or hybrid approaches, requiring PMOs to evolve from traditional oversight functions to dynamic enablers of delivery. PMOs will need to provide flexible governance frameworks that support both speed and accountability, acting as a bridge between leadership and delivery teams.

Key takeaways from recent observations highlight that PMOs must:

- Focus on value over compliance: The PMO’s role will increasingly emphasise driving tangible benefits for the organisation rather than purely monitoring adherence to process.

- Enable informed decision-making: By providing timely, clear insights into risk, progress, and resource allocation, PMOs can empower leaders to make strategic decisions even in uncertain contexts.

- Support hybrid delivery models: With the shift to Agile or hybrid approaches, PMOs will need to adapt tools, reporting, and governance to suit iterative delivery while maintaining oversight.

- Champion capability and culture: Beyond process, PMOs will play a critical role in shaping organisational capability, fostering collaboration, and embedding a culture of learning and resilience.

- Operate as a hub for stakeholder engagement: Acting as a single source of truth, the PMO ensures alignment across multiple initiatives, connecting executives, delivery teams, and external partners.

Looking forward, PMOs that embrace flexibility, value creation, and adaptive governance will be best placed to support organisations in navigating complexity, uncertainty, and accelerated change. The PMO is no longer just a control function; it provides practical support to keep projects on track and the organisation responsive.

AUTHOR: STEPHEN HALPIN

What role will public servants play in an AI connected world? Nearly 700 million people use AI each week, and the Australian Government has just launched its own sovereign-hosted instance of GPT-4o.[1],[2] Within the APS, 70% of staff believe AI will transform service delivery and policy.[3] Yet that optimism must be tempered by the lessons of previous attempts at automation such as Robodebt, underscoring the need for strong ethical guardrails that maintain public trust.

Industry’s embrace of AI shows what’s possible. Medical researchers have shortened drug discovery timeframes, farmers use real-time monitoring to boost crop yields and conservation efforts, and health professionals see more patients by reducing administrative burdens with AI.[4] But disruption and unintended consequences have followed. In professional and financial services, clients may now receive a report in minutes which once took junior consultants’ weeks to prepare.[5] AI is also making inroads into the care economy with therapy bots offering scripted counselling, and social media platforms building AI “friends” to counter loneliness.[6]

The individual’s use of AI is the precursor for successful government deployment. Cultural readiness allows the promise of AI efficiency to be realised. We can see that people are using AI for a range of topics; health, education, and general learning. Its application promises efficiency, not for its own sake, but to free up public servants to spend more time engaged in the complex thinking needed to address important social problems.

A note on method

For this article, we conducted an analysis of open-source AI model training data. We algorithmically clustered prompts into statements with a common theme. For example, “medical, doctor, symptoms, patient” and “earth, planet, sun, solar”. Clusters were randomly chosen and analysed against Bloom’s Taxonomy, a framework for classifying classroom learning objectives by cognitive complexity. Basic knowledge, or lower order thinking, is categorised as remembering, understanding and applying. Higher order thinking is categorised as analysing, evaluating and creating. [7]

Findings

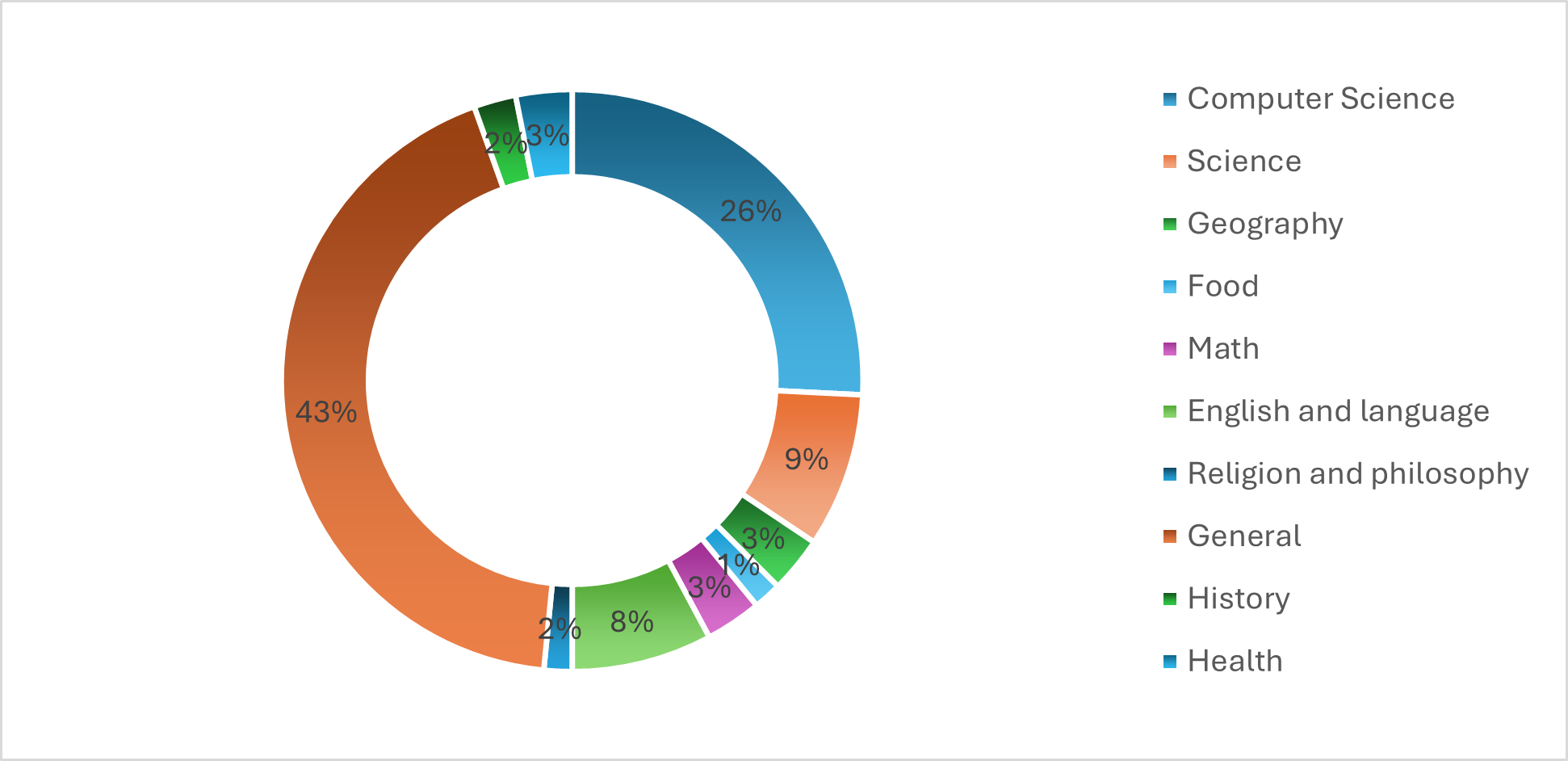

Twenty-six percent of prompts relate to computer science and technical how-to in Python, React, JavaScript, and networking. Eight percent cover English and language, including essay writing and text interpretation. Math and science make up 12%. But the largest share—43%—involves general conversation with the AI: polite interactions, jokes, gift ideas, film recommendations, and personal questions.

Figure 1: How people are using AI

The taxonomy mapping shows most people use AI to “remember” or “understand” information, i.e lower order thinking. The analysis showed very little use of AI for higher order thinking.[8] For example:

- 82% of prompts in the “AI, intelligence, artificial” category asked for explanations or recalling of facts;

- 70% of “book, summary, plot” prompts sought timelines or thematic insights; and

- 96% of “medical, doctor, symptoms” prompts requested treatment details

A word search spanning all 15,200 prompts for “government,” “department,” “agency,” and “public service” yielded just 55 results (0.36% of the sample). Eight of the 55 asked for agency or policy information and the rest related to political science or historical facts. This suggests people either don’t realise AI can deliver government services or didn’t need them in this sample.

Implications for the public service

AI could shift government’s front door services from digital to artificial. The breadth of topics in the dataset shows people trust AI with medical, personal, and social issues. With the right model, AI could handle many administrative, in-person, and phone queries, and would be limited only by computational power. Lengthy delays could disappear in front line areas like the NDIS, Veterans’ Affairs, Centrelink and Health and Ageing.

Within agencies, AI could take over the lower order thinking tasks in policy and regulation. Recalling past decisions, preparing minutes and records, compiling statistics, or drafting background material for briefings could all be undertaken by a well-trained model. An AI integrated with enterprise data could also retrieve decades-old institutional knowledge in seconds. Retirements and staff movements would no longer erase critical history.

Government IT projects could also benefit. Many prompts within the dataset analysed involved Python, JavaScript, and machine learning questions. AI could streamline development by reducing code review, debugging, and training time. Smaller teams could build and test faster, delivering products on schedule.

What’s left for humans?

If AI assumes responsibility for gathering fundamental information and undertaking routine tasks, public servants can focus on creativity, higher-order thinking, evaluation, and analysis. In practice, this could mean uninterrupted time to review literature from academics, industries and other governments. Economic models and business cases can be informed with richer real-world data, with teams directing efforts towards closing data gaps rather than making assumptions.

Positioning AI as the first point of contact for government could also free up frontline areas to work on more complex cases that require judgement and empathy. Claims that traverse portfolio areas could be linked to a single customer service agent for resolution. Social policy experts could meet and collaborate in the same way medical teams do to deliver high-quality continuity of care.[9]

One of the most surprising findings was how often people socialised with AI. Gift suggestions for anniversaries, mothers’ day, valentines and first dates made up an entire category. Turning to AI for advice on presents suggests a shift in how people seek advice and connection. This is no different in the public service, which relies on the communication of ideas across sections and divisions. The public service often struggles with this and is criticised of siloed working. If AI takes over transactional tasks, engagement and collaboration must become the public services’ cornerstone, at least until Artificial General Intelligence (AGI) arrives and we can ask it to fix our deepest problems.

And whilst AGI may one day transform how we work and live, the immediate priority is integrating today’s AI responsibly into government services. Understanding how to wield this readiness to automate lower-order tasks that are repetitive and transactional will free public servants to work on higher-order challenges; the complex, cross-portfolio issues that require deep analysis, collaboration and creativity. For leaders in the public service the short term goal is clear: ethically shepherd adoption and invest in capability and AI deployment that elevates, rather than erodes, the human role in public service.

[1] https://www.cnbc.com/2025/08/04/openai-chatgpt-700-million-users.html

[2] https://www.itnews.com.au/news/gov-quietly-launches-onshore-instance-of-gpt-4o-for-aps-618944

[3] https://www.themandarin.com.au/296879-public-servants-positive-about-ai-use-in-service-delivery-mandarin-survey/

[4] https://www.industry.gov.au/publications/australias-artificial-intelligence-ecosystem-growth-and-opportunities

[5] https://www.thefp.com/p/the-consulting-crash-is-coming

[6] https://sfist.com/2025/05/01/mark-zuckerberg-gets-roasted-for-saying-the-average-american-has-fewer-than-three-friends-while-pushing-ai-chatbots/

[7] https://www.monash.edu/learning-teaching/TeachHQ/Teaching-practices/learning-outcomes/how-to/align-with-taxonomies

[8] ibid

[9] https://www.health.gov.au/our-work/strengthening-medicare-measures/encouraging-multidisciplinary-team-based-care

AUTHOR: AARON GREENMAN

Governments around the world including Australia have embraced responsible AI policies grounded in ethics, transparency, and public trust. But while caution is warranted, inaction also carries risk. As expectations grow and AI capabilities accelerate, slow adoption can erode government relevance, capability, and credibility. The goal for government shouldn’t be to eliminate AI risks entirely, but to manage them responsibly while keeping pace with the community’s needs. This includes reducing over-reliance on external technology vendors and building internal capability to steer and govern AI effectively.

The principles might be appropriate, but are they enough?

Over the past two years in particular, the Australian Government has made real progress in setting strong foundations for responsible AI. Agencies have published transparency statements, appointed accountable officers, and committed to ethical principles such as human oversight, explainability, and fairness. The Digital Transformation Agency’s AI policy and classification framework has provided helpful structure. Most federal agencies currently use AI in low-risk domains: automating internal workflows, summarising documents, analysing policy data, or powering staff-facing virtual assistants.

This measured and principled approach is commendable and necessary. However, principles without increased momentum may soon become a liability. The public sector faces an emerging challenge: how to operationalise AI principles at scale and speed, without compromising trust. The truth is, while governments are moving carefully, the world around them isn’t slowing down.

The emerging risk: what happens if we move too slowly?

Playing devil’s advocate, it’s worth confronting an uncomfortable truth: being too risk-averse with AI can create new forms of risk. Here’s how:

First, there’s the issue of service experience. Citizens increasingly expect the same level of responsiveness and personalisation from government that they get from the private sector. When accessing health, welfare, or tax services, people want accurate, timely, digitally enabled experiences. If government systems feel slow, disconnected, or hard to navigate, trust erodes, not just in the service, but in the institution itself.

Second, there’s the missed opportunity for productivity. AI has the potential to automate low-value tasks, freeing up public servants to focus on strategic, high-impact work. Without it, inefficiencies compound. Staff remain bogged down in administrative burden, innovation slows, and the public sector struggles to keep pace with demand.

Third, regulatory and policy expertise is at risk. As AI becomes embedded in every sector, from finance to defence, governments need operational literacy to regulate, audit, and respond effectively. Agencies that haven’t strategically implemented AI internally, may find themselves ill-equipped to govern its use externally.

Fourth, there’s the talent challenge. Public servants want to do meaningful, future-focused work. If the public sector is perceived as behind the curve, it risks losing, or failing to attract skilled technologists, analysts, and innovators to industry or overseas markets.

Finally, and perhaps most urgently, there is growing concern, particularly following recent developments overseas, about third-party entities wielding disproportionate influence over public sector AI systems. As governments outsource capability to commercial providers, they may inadvertently cede control (or visibility) over core decision-making processes. This includes dependency on proprietary models, limited transparency into algorithmic behaviour, and constrained ability to explain or audit outcomes.

This underscores the need for robust in-house capability. Agencies must be able to assess, adapt, and govern AI tools, not just procure them. Otherwise, governments risk becoming passive users of someone else’s technology, rather than active stewards of their own digital future.

How other governments are moving responsibly but assertively

While current Australian government AI use largely remains assistive, supporting, rather than replacing human decision-making, there is a noticeable lack of adoption of agentic AI systems capable of autonomous planning and action. Yet, opportunities abound in well-governed deployments and globally, leading governments demonstrate that responsible yet assertive AI adoption, including agentic AI, is achievable and beneficial.

For example, New Zealand has implemented agentic AI with its SmartStart platform, where AI proactively registers births, schedules healthcare appointments, and coordinates associated social services automatically.

In Singapore, agentic AI systems coordinate real-time traffic management, dynamically responding to changing conditions and improving congestion outcomes.

Estonia uses an agentic AI that proactively helps citizens navigate and complete complex administrative processes across multiple government services.

These international experiences provide valuable insights into safely and effectively deploying AI that doesn’t just assist human tasks but autonomously performs complex public-service functions, offering practical lessons for Australia’s own strategic AI adoption.

These examples show that strategic, experimental, and iterative AI adoption is possible. The key is to be strategic and pair innovation with accountability, starting with modest, measurable pilots, applying proportionate controls, and building internal literacy alongside technical tools.

Bridging the trust gap: practical moves for government

Governments don’t have to go all-in on AI overnight. But they must start moving faster and smarter. That means:

- Begin with internal, assistive use cases such as content summarisation, translation, policy drafting, or document classification, which provide immediate productivity gains and build internal confidence.

- Pilot AI tools in controlled environments including sandboxes, trials, and internal settings, with clearly defined metrics, transparent oversight, and thorough evaluation processes to identify opportunities and challenges early.

- Strategically plan for AI adoption by clearly identifying and prioritising use cases that offer tangible value. This includes defining specific roles, boundaries, and oversight mechanisms for agentic AI systems to avoid unchecked autonomy, particularly in sensitive areas like welfare or healthcare decision-making.

- Clearly delineate the scope and autonomy boundaries for agentic AI deployments, ensuring these systems augment rather than replace human judgment in critical processes. For example, agentic AI could proactively streamline administrative services or environmental monitoring while explicitly leaving final decisions and sensitive judgments in human hands.

- Develop multi-disciplinary teams comprising technologists, policy experts, legal advisors, ethicists, and domain specialists to provide comprehensive governance across AI deployments, ensuring ethical considerations and transparency remain central at every stage.

- Adopt tiered risk frameworks that tailor oversight and governance to the level of potential risk and impact, enabling responsible but agile implementation rather than uniform, overly cautious approaches.

- Enhance AI procurement literacy, empowering agencies to critically evaluate third-party solutions, insist on transparency, and embed public-interest protections directly into contracts.

- Invest proactively in workforce training, transitioning staff from foundational AI awareness to advanced model risk assessment capabilities, ensuring public servants are equipped with both policy literacy and technical fluency.

- Establish dedicated AI assurance functions to rigorously review, continuously test, and audit AI systems, particularly agentic tools, maintaining accountability and public trust throughout the AI lifecycle.

To support these shifts, certain prerequisites are essential:

- Clear governance arrangements: Agencies must define enterprise-wide structures and assign AI-specific accountabilities and responsibilities, including at the model and system levels.

- Data ethics integration: A consistent data ethics framework needs to be embedded across AI lifecycles, with reproducibility, auditability, and transparency integrated into model design.

- Policy and procedural alignment: AI development and use must align with existing organisational policies, supported by targeted procedures for AI-specific risks.

- Performance measurement: Agencies should establish clear mechanisms to evaluate AI’s effectiveness, impact, and compliance across time

- Risk and assurance frameworks: AI-related risks, including misuse of data and unintended outcomes, must be assessed through enterprise risk management processes, with appropriate controls in place

These recommendations, drawn from the Australian National Audit Office (ANAO) review of ATO’s AI practices[1], reinforce that effective adoption requires more than tools, it demands culture, capability, and control.

Most importantly, agencies must ensure that any AI system they use, whether developed in-house or by a vendor, remains within their control, explainability, and accountability.

[1] Governance of Artificial Intelligence at the Australian Taxation Office | Australian National Audit Office (ANAO)

AUTHOR: JULIE BAKER

With over 15 years of experience in internal audit I have gained firsthand insight into the transformative role of internal audit. My current role is at Sententia Consulting in the internal audit service line and previously I held a Chief Audit Executive (CAE) equivalent role in the ACT Government. My passion for the profession stems from the powerful impact we have in enhancing organisational processes and offering invaluable insights into the health of an organisation.

The introduction of the new Global Internal Audit Standards (the Standards), effective January 9, 2025, marks a significant milestone for the internal audit profession. These Standards add a new layer of rigor to our profession and underscore the importance of maintaining the highest standards of professionalism in our work. As internal auditors, it is crucial that we not only understand these changes but actively embrace them to fulfill our obligations.

In this article I explore two key components that not only highlight important changes but also reflect the evolving demands placed on CAE’s to shape the future of the internal audit function

CAE Reporting to the Board and Senior Executive

One of the most prominent changes introduced by the Standards is the expanded scope of CAE reporting to the Board and Senior Executive. Historically, CAEs have reported critical aspects of the internal audit function, including:

- The Internal Audit Work Program (IAWP)

- Budget management

- Audit Charter

- Any disagreements between the CAE senior management on scope, findings or other aspects of the engagement, among other things.

However, the new Standards require CAEs to include additional elements, such as:

- The IAWP discussions with the Senior Executive

- Evaluating the adequacy of resources, including technological resources, and strategies to address shortfalls

- CAE qualifications and competencies

- Developing an Internal Audit Strategy that outlines future direction.

These new requirements provide an opportunity to further elevate the professionalism and transparency of the internal audit function. However, they also introduce new challenges – particularly in how we engage with the Senior Executive. Below is my take on these requirements from the perspective of a CAE.

Discussing the IAWP with the Senior Executive

As a CAE, I have witnessed firsthand the impact that discussions with Senior Executives can have on the independence of the IAWP. I have found that Senior Executives and Branch Heads often provide a mix of valuable insights into topics, but they may also suggest their own area not be audited or provide reasons for delays. More importantly if Senior Executives expect they can shape the IAWP, it can jeopardise its independence. To maintain independence, I recommend an IAWP process that includes:

- Interviewing Senior Executives (including branch heads) to gather potential IAWP topics.

- Compiling and ranking the suggested topics with the input of external Audit and Risk Committee (ARC) members.

- Submitting the draft IAWP, based on ARC members rankings for discussion at the ARC.

- Finalising the IAWP based on the ARC’s feedback.

By clearly defining the role of the Senior Executive in IAWP discussions it is possible to gain valuable insights into specific topics across the organisation, while safeguarding the independence of the IAWP.

Evaluation of resources and addressing shortfalls

The Standards include a requirement for CAEs to carry out an evaluation on resources with a strategy including how to address shortfalls. A common tension for CAEs is managing limited resources while delivering the IAWP. Whether it is technological tools or personnel, this balance can be challenging. In my experience, resource shortfalls were better addressed through managing expectations rather than seeking additional funding.

I focused on optimising existing resources, managing what I had and taking a proactive approach to avoid shortfalls in audit delivery. Resource allocation began with the number of audits in the IAWP and budgeted days. Some audits were high level and others deep dives. My scopes were broad, budgets modest, the topics complex and the time to carry out the work was limited. I had a

government panel of providers that expanded from 7 to 12 service providers.

Methods I used to optimise audit outcomes within existing resource levels included:

- Sending requests for services (RFS) to a group of providers with prior knowledge of the organisation as this knowledge is beneficial.

- Carefully evaluating submissions to ensure the offer clearly aligned with my needs and proposed staff were appropriately experienced.

- Attending entry and exit meetings and always listening to all contributions with a lens of improving practices across the organisation.

- Holding a preliminary meeting with the assigned service providers prior to exit meetings with business areas to understand progress and findings and ensure the scope had been fully addressed.

- Reviewing the draft report before it was distributed more broadly, ensuring it could be understood by readers unfamiliar with the content and that recommendations were beneficial and allocated to the right section to support a smoother review process with business areas.

For me, these practices were requirements for all internal audit reports, regardless of the budget, to support clear oversight and enable the management of expectations to get quality outcomes with limited resources.

From a broader perspective, addressing technological resource gaps does not necessarily mean acquiring bespoke internal audit tools. When relying on outsourcing internal audits to service providers, the service providers use the internal audit tools available to them. When performing in-house internal audits, the tools available within the Microsoft Office suite are usually sufficient to manage the process when used effectively, demonstrating that technological resources do not have to be elaborate. Regardless of the resources available, the key to overcoming technological

resource challenges is utilising what is available and communicating with senior leadership regarding what is realistically possible.

CAE qualifications and competencies

Another significant change is the reporting of CAE qualifications and competencies to the Board and Senior Executive. While qualifications and competencies were always an expected part of the CAE role, they were not typically reported to the Board. The new Standards suggest the Board approve the CAE’s job description and encourage pursuit of opportunities for continuing professional education,

membership in professional associations and opportunities for professional development.

This shift raises important questions about the role of professional development and the value of qualifications versus on-the-job competencies. It seems to me that these suggestions imply that if competencies were the reason for the CAE appointment, then there is an expectation qualifications would follow. From my experience, CAE qualifications are an important factor in establishing credibility, but the ongoing development of competencies is equally critical. The Standards suggest that Boards encourage continuous professional development, which is a positive step toward fostering a culture of learning and growth within the internal audit function.

The requirement to report CAE qualifications and competencies to the Board leaves me wondering what form this could take. I see delivery of the IAWP, including the quality of the internal audit reports and secretariat function as practical measures of the competencies.

Would the reports include:

- A CV listing CAE qualifications and work experience.

- The CAE’s ability to resolve action items from ARC meetings

- On the job training provided to the team

- A combination of all these factors?

Would it be self-reporting? Or would it be a survey of key stakeholders like the Board Chair, Senior Executives, selected service providers and the internal audit team? Consider the scenario, given the bias often held against internal audit – How would recommendations that improve practices across the organisation, but increase the workload for a Senior Executive be reflected in a CAE competency review?

It is my view that all these considerations would need to be factored in to make reporting CAE qualification and competencies have real value.

Developing an Internal Audit Strategy to deliver the Internal Audit Work Plan

One of the new requirements in the Standards is the formal expectation for CAEs to develop an Internal Audit Strategy that aligns with the organisation’s strategic objectives. This strategy should detail how the IAWP will be delivered and ensure that the internal audit function supports broader organisational goals.

When I was first tasked with developing an internal audit strategy, it was at the

request of a five-year external assessment of my internal audit function. Once I created the strategy, it became an invaluable tool for guiding the internal audit function and ensuring that the team was aligned with both internal and external expectations.

My strategy included elements such as:

- Vision and mission for the internal audit function

- Delivery methods (including the management of external service

providers). - Timelines for IAWP, Charter review and approvals and financial

statement reviews - Budget management processes and tracking

- Recommendation implementation tracking and reporting

- The Board Secretariat.

While my internal audit team was relatively small, creating a strategy helped ensure that team members understood their roles and expectations. It also made it easier to communicate with senior management and the Board, fostering a more transparent and collaborative relationship. Now, with the new Standards, this strategic approach is a requirement for all CAEs, regardless of the size of the

internal audit function. Embrace the strategy as a beneficial, centralised document containing the internal audit function deliverables.

Act Now

The new Standards present both opportunities and challenges for CAEs. The expanded reporting requirements and the development of an Internal Audit Strategy are essential for ensuring that internal audit functions are aligned with organisational goals and are delivering value. However, these changes also require careful thought, especially regarding the independence of the IAWP, resource

management, and the reporting of qualifications and competencies.

As CAEs, we must be proactive in understanding and implementing these new requirements. The Standards provide an opportunity to further elevate the internal audit profession and demonstrate the value we bring to organisations. By embracing these changes and leading the internal audit function with transparency, professionalism, and foresight, we can build stronger relationships with governance bodies and enhance our ability to add value to our organisations.

It’s time to act now—to align ourselves with the new Standards and ensure our internal audit functions are equipped for success. Let’s take this opportunity to advance our profession and continue to drive meaningful impact in the organisations we serve.

If you would like any additional information contact Sententia Consulting on Sententia@sentcon.com.au.

AUTHOR: KIRSTY WISDOM

It’s internal audit program planning season! As internal audit consultants we get the opportunity to work with a variety of diverse organisations auditing a wide range of different topics. This gives us unique insight into trending topics and common issues that might be worth considering for your organisation.

If you’re working in the public sector, it will probably come as no surprise to you that areas like integrity, climate change risk management, third party risk management, information management, artificial intelligence, and conflicts of interest are finding their way onto a lot of audit programs – and for good reason. These are areas of emerging risk and increasing public scrutiny that are timely to seek some assurance confidence over. Here we outline some the common pitfalls that are worth considering when auditing these trending topics and how to avoid them.

Integrity

Across the broader Australian Public Service (APS), there has been a marked increase in the attention and emphasis directed toward the concept of integrity. This focus was initially driven by the Independent Review of the APS (the ‘Thodey Review’) in 2018 and is central to the current APS reform agenda which includes a priority area focused on promoting “an APS that embodies integrity in everything it does”.

Everyone knows that integrity is a hot topic, but the main pitfall we see is simply uncertainty about how to actually embed it, and even more uncertainty about how to provide assurance over it. For agencies that have started to dip their toe in the water of auditing integrity, the initial focus tends to be on assessing whether good policies/procedures/training etc. are in place – i.e. – “are we saying the right things?”. This is an important place to start, but the real challenge comes in understanding whether people are doing the right things and acting with integrity in practice.

Starting small with a relatively high-level framework-based review will still deliver value. Auditing integrity in any way helps to demonstrate that it is an organisational priority and will start to get people thinking about what it means to be held to account for an integrity culture. To get the most value out of this type of review, it is important to consider how well messaging is tailored to the actual organisational context (and the different contexts within the organisation) to support staff to understand integrity as an everyday consideration rather than an abstract concept.

But to start to get assurance over the integrity culture in practice, auditors need to consider broader techniques such as surveys, staff interviews, focus groups, behavioural observation, and business context analysis. This too can start relatively high level to get initial insights and inform future planning for more targeting reviews. Where integrity culture is a high priority and higher assurance confidence is desired, a more robust and repeatable program of integrity culture audit can be developed. To get value from these more comprehensive audits, it is crucial to define and agree what a good integrity culture looks like for that organisation, including key desirable and undesirable behaviours, to provide a consistent baseline against which to compare.

Climate change risk management

The introduction of climate disclosure reporting requirements for Commonwealth entities has boosted climate change risk management up the agenda from an assurance perspective. The main pitfall we’ve noticed in this case is a focus purely on ensuring preparedness for compliance with the new requirements. Although this is important, internal audit functions should take this opportunity while climate risks are front of mind to promote and explore other aspects of climate risk management that are important organisational considerations.

Depending on the nature of the organisation, additional aspects that should be considered include how climate risks may impact Work Health and Safety, Business Continuity Planning, and Disaster Recovery Planning. Have these policies and the associated risks and controls been re-assessed in light of a changing climate and more regular extreme weather events? Does the organisation have clear rules and guidance in place around things like extreme heat and are these understood and implemented in practice?

More broadly, have climate change risks been considered strategically where they may have a direct impact on agency goals? Have these risks been factored in as part of development of strategies and goals, and are they considered on an ongoing basis? The nature of these risks will vary greatly between organisations, but there are potential impacts to consider across health and social outcomes, infrastructure, productivity, service delivery and more that will be relevant for various public sector agencies.

In considering climate change related risks, specific expertise is generally required to ensure an audit is sufficiently robust to provide more than surface level insights. Such expertise supports the audit team to more effectively challenge management assumptions were needed and ensure risks are fully understood and nothing is missed. For this reason, including a subject matter expert as part of the audit team is crucial to ensuring value.

Third-Party Risk

Outsourcing, shared services, and reliance on third-party providers are now entrenched features of federal government operations. Whether it’s IT infrastructure, defence procurement, health services, or consulting engagements, third parties are often integral to delivering core functions. However, although you can outsource services, you cannot outsource risk.

The key pitfall we come across in auditing third-party risk is confusion around the concept itself and who is actually accountable and how these risks can and should be managed. Unfortunately for the public sector, the public don’t much care for excuses. Even if the issue was 100% the fault of the third party – how could the government have allowed this to happen? Why weren’t you monitoring it? Why didn’t you do your due diligence? Again, you cannot outsource your risk.

Third-party risk is multifaceted – spanning performance, cyber security, ethical conduct, compliance, data privacy, and financial integrity. Failures by external partners can have significant consequences for service delivery and public confidence.

As a result, internal audit must ensure that third-party governance frameworks are robust, including due diligence processes, contract management practices, and monitoring mechanisms. This also extends to sub-contractors, where transparency and accountability may be further diluted. Third-party risk is a crucial topic to audit to help agencies understand their risk profiles and identify improvement opportunities. Auditors can add further value by treating stakeholder engagement throughout the audit process as an opportunity to educate on accountabilities and expectations to support improved understanding and risk culture as this capability gap tends to be the main barrier to strong third-party risk management.

Information Management

Information is one of the most valuable assets in the modern public sector. Information management refers to the creation, description, preservation, storage, protection, usage, disposal, and governance of digital and non-digital records and data that are relevant to the operation of an entity. Good information management maximises the value of an agency’s information assets by ensuring they can be found, used and shared to meet government and community needs and support the efficient and effective delivery of outcomes.

This is relatively well understood across the public sector, and as a result, information management is a regular feature on audit programs. There are plenty of useful and detailed standards that can be applied such as the Information Management Standard for Australian Government which align to obligations under the Privacy Act and Archives Act that make for a relatively straightforward audit. But there is one crucial element that these “straight forward” information management audits ignore – people. In our experience, the biggest risks from an information management perspective are not systems, but people. We’ve seen agencies with world class systems and processes and well-tested system controls – where staff save everything offline on their desktop and make endless use of workarounds to avoid ever having to touch that world class system.

This human side of information management is crucial to consider in the design and delivery of an information management audit to get a true understanding of risk levels and effectiveness.

Conflicts of Interest

Conflicts of interest, whether real or apparent, can undermine the credibility of government decisions. In a public sector context, where impartiality is paramount, even the perception of bias or favouritism can erode trust. From procurement panels to grant allocations and recruitment decisions, conflict of interest risks can be found across everyday government operations. Recent scrutiny around conflicts of interest in the public sector has pushed COI onto the agenda for many audit committees.

There are some common pitfalls we have noticed that should be considered when scoping an internal audit. Most agencies have a decent COI Policy, with COI built into annual training programs – but this is really the bare minimum. Implementation and truly embedding understanding of COI into business as usual is where it tends to come unstuck.

For example, it is worth remembering that the relevant requirements under the Public Governance Performance and Accountability (PGPA) Act, and PGPA Rule are mostly not framed around conflicts of interest, but rather disclosure of any material personal interests. The intent is to manage real or apparent conflicts – but a lot of agencies seem to place such a focus on conflicts that they forget that disclosure requirements relate more broadly to any material personal interests.

As a result, material personal interests tend to only be considered in individual contexts in case there is a potential conflict there. Disclosure processes are often completely disjointed or siloed with no central repository or visibility across the organisation. But the people making the disclosures don’t always know that and often assume if they have disclosed an interest in one place for one purpose, then they have ticked off on their duty.

In auditing conflicts of interest management, particular attention should be paid to whether/how personal interest declarations are managed holistically. Additionally, it is very difficult to audit whether appropriate interests have been declared – as auditors simply don’t know what they don’t know. We can audit whether declarations that have been made have followed appropriate processes, but what about declarations that weren’t made? An element of culture-based audit utilising techniques like surveys or interviews can be useful to provide additional insight on this aspect.

Artificial Intelligence (AI)

AI is the word on everyone’s lips as the power and prevalence of the technology continues to expand. In the public sector, there are rightly concerns around how and when AI can or should be used while maintaining integrity, protecting privacy, and meeting community expectations and legislative obligations (noting that most program legislation was not drafted to cater for AI). However, most agencies are already using AI in some capacity and planning to increase usage. As a result, audits of AI governance are popping up as a high priority.

Drawing on recently released whole-of-government guidance like the Australian Government Policy for the responsible use of AI in government and the Australian Government AI Assurance Framework, audits tend to focus on agency policies and governance arrangements for the design, development, deployment, monitoring and evaluation of agreed use cases.

Although this is of course crucial, a key element that is not always captured or considered are the unapproved use cases that the agency might not even be aware of as staff look for ways to increase efficiency in their day-to-day workflows using publicly available tools. Internal Audits of AI governance should include consideration of broader AI culture across an agency and how risks around “shadow AI” from unauthorised individual use cases are understood and mitigated.

The Sententia Consulting team recently traded laptops for sunhats and headed to beautiful Manly for our annual company retreat — and this year, it was something truly special.

Framed by blue skies and golden beaches, our retreat provided more than just a change of scenery. It offered a rare and valuable opportunity to pause, reflect, and reconnect — not only with each other, but with the values and vision that continue to drive us forward. From the moment we arrived, it was clear this wasn’t just another offsite — it was a celebration of how far we’ve come, and a springboard into everything that lies ahead.

![]()

Marking a Milestone: 5 Years of Sententia

This year holds particular significance for our firm, as we celebrated five years in business — a major milestone that reflects not only the success of our work, but the passion, trust, and dedication of every single person who has been part of our journey. In an industry that’s constantly evolving, reaching the five-year mark is a meaningful reminder of the strength of our foundations and the clarity of our vision. It’s been five years of building relationships, delivering impact, and growing a business that we’re genuinely proud of.

Welcoming New Faces, New Ideas

As a fast-growing firm, one of the most energising aspects of this year’s retreat was the presence of so many new team members. Over the past year, we’ve welcomed a number of talented individuals into the business — each bringing fresh perspectives, diverse experiences, and new energy to our work.

The retreat created space for these new connections to form organically. Whether it was over strategy sessions, team-building exercises, or simply beachside coffees, it was inspiring to watch people from different parts of the business come together, share ideas, and start to shape our next chapter. Moments like these are when culture is built — not through policies or slogans, but through genuine human connection.

![]()

![]()

Reflecting, Realigning, Recharging

A core part of our retreat was taking time to reflect on where we’ve been, where we are now, and where we’re going next. Through facilitated strategy sessions and open team discussions, we explored our vision for the future and aligned on the big goals ahead.

These conversations weren’t just about strategy documents or quarterly objectives — they were about values, impact, and how we want to show up for our clients, our communities, and each other. In the fast pace of day-to-day work, it’s easy to focus on outputs. But this retreat reminded us of the importance of stepping back to focus on why we do what we do, and how we do it together.

Building with Purpose: Our Partnership with the WaterWorks Program and Pinnacle

One of the most memorable and meaningful parts of the retreat was a hands-on team-building session facilitated by Pinnacle and the WaterWorks Program. During this session, our team collaborated to build six emergency water filters — each one destined for a community in Uganda where access to safe, clean drinking water remains a daily challenge.

This wasn’t just a powerful team exercise — it was a tangible reminder of how our efforts, even from afar, can make a real difference. Each filter we constructed has the capacity to provide clean water to a family for up to five years. To know that something built with our own hands could help protect the health and dignity of others around the world added a deep layer of meaning to our experience.

In addition to the emergency filters, Sententia Consulting has also contributed to the installation of permanent water filtration systems in Uganda — supporting longer-term access to safe water across several communities. These initiatives align with our belief that businesses have a responsibility to create positive impact beyond profit.

A Surprise to Remember: Cruising Sydney Harbour

Just when we thought the retreat couldn’t get any better, the team was surprised with an unforgettable evening: a private chartered boat on Sydney Harbour to celebrate our five-year milestone in style.

As the sun set over the skyline, we shared drinks, stories, and laughter on the water — taking a moment to breathe in the beauty of the city and the significance of what we’ve built together.

Huge thanks to Karisma Cruises for helping bring this magical evening to life. From the warm hospitality to the amazing food and seamless experience, it was the perfect way to mark such a meaningful moment in our journey.

![]()

The Road Ahead

We left Manly feelingre-energised, refocused, and deeply grateful. It’s easy to get caught up in the busyness of the everyday, but experiences like this retreat serve as a powerful reminder of who we are and what we’re building — together.

As we look ahead to the next five years, we’re more committed than ever to continuing to grow with intention, stay curious, and deliver meaningful results for our clients – and doing so in a way that keeps people and purpose at the centre of everything we do.

To everyone who made this retreat possible — thank you. And to the whole Sententia Consulting team, past and present — here’s to everything we’ve achieved so far, and to everything still to come. Cheers to the journey. 🥂

AUTHOR: DAVE HADDAD & SEAN MALONEY

Across the broader Australian Public Service (APS), there has been a marked increase in the attention and emphasis directed toward the concept of integrity.

This increased focus on integrity within the APS was initially driven by the Independent Review of the APS commissioned by the then Government in May 2018. The Review’s Final Report was delivered in 2019 and included a recommendation aimed at reinforcing APS institutional integrity to sustain the highest standards of ethics. The intention is to develop a pro-integrity culture within the APS, and work is still underway for this to be achieved. In October 2022, the Albanese Government announced its APS Reform agenda to further strengthen the APS. This agenda includes four priority areas, the first of which is an “APS that embodies integrity in everything it does”. Against this backdrop, there may have never been higher expectations placed upon public officials to conduct themselves with integrity.

To support public officials who are continuing to grapple with this increase in scrutiny and expectations, the APS has established principles and frameworks to direct and govern behaviour, that are aligned to legislation such as the Public Service Act 1999 and the Public Governance, Performance and Accountability Act 2013. These supports include defined whole-of-government standards such as the APS Values and APS Code of Conduct and are supplemented by agency specific corporate and HR policies.

But the success of these mechanisms is contingent upon, and may be limited by, their embrace and fulfillment by leaders. To effectively support the establishment of a pro-integrity culture and in order to encourage pro-integrity behaviour across the APS, it is integral to start at the top. The tone and values set by leadership, and the extent to which they are overtly espoused and lived up to, lays the foundation for a Pro-integrity culture and values-based behaviour.

In undertaking any assessment of whether leaders and leadership are positively impacting integrity culture, the following concepts are crucial to consider:

- The clarity of values-based communication from leaders.

- How staff perceive leadership’s expectations regarding integrity.

- The consistency of behaviour under pressure.

- How leaders handle their missteps.

The clarity of values-based communication from leaders.

As outlined earlier, tools and guidance have been developed with an intention to support consistent principles-based behaviour across the APS. However, as with many high-level policies intended to be broadly applicable, these constructs and concepts may be difficult for staff to translate and apply in their day-to-day roles. Many APS staff may in fact struggle to name all of the APS Values, or all elements of the APS Code of Conduct.

To bring integrity into practice, we must think at a more personal level. The behaviours and values of those we work amongst are easy to recognise and reflect. This is where leadership can start bringing conceptual integrity into practice. Convention says that culturally tone is set at the top, so it is imperative that leaders have a defined and, most importantly, well-communicated set of values.

So, while most leaders reflect on the question “What are my values?”, it is just as important to reflect on “Have I effectively communicated these values?”. In assessing the effectiveness of communication relating to values, the following should be considered:

- Has it been explicitly stated that something is right and/or if something is wrong?

- Is communication overt, public facing, and/or easily accessible?

- Is values/integrity related communication consistent in its messaging?

How staff perceive leadership’s expectations regarding integrity.

While the point above speaks to the efforts made by leaders to be effective in their communication, a key component of communication is in how it is received. The reception of this information, and how its messaging is perceived by staff, is the link between communication and improved behaviours. Determining whether this has occurred involves establishing if staff’s perception of what is right vs what is wrong, or what the important values to a team are, aligns to the expectations communicated by leadership.

Evaluation or reflection can help to identify, and subsequently rectify, any disconnects emerging in this space. This evaluation can be done by leaders or by anyone looking to review the impact of values and behaviours on integrity. It can be done through formal interactions, via structured data gathering activities or through informal conversations and observations. These activities should be looking to assess and consider the alignment of the values intended to be communicated by leadership and the perceptions of others.

Continual investment in understanding perceptions is important as it is these perceptions that are most likely to inform and drive behavioural change. This feedback should help to inform leaders of adjustments that made need to be made to their communications to support aligning perceptions with their intended outcomes.

The consistency of behaviour under pressure.

While developing a coherent set of values is integral in establishing a pro-integrity culture, consistency is how these become embedded in the mindset and behaviours of teams. Discussing and working in alignment with a strong set of values is far easier in a business-as-usual operating environment. Through consistent messaging and consistently living up to this messaging even in challenging moments, leaders can highlight the importance of the values they preach and set an example for their teams to reflect.

In reviewing the impact of leadership on driving improvements in integrity, this is the most important component to evaluate. When reviewing the behaviours and messaging of leadership, it may be complex to decipher intended messaging or how values are being communicated. It is much easier to assess if there is consistency in this messaging:

- Are the same things being prioritised/communicated?

- Is it easy to align values focused communication with current behaviours?

- Do decisions made under pressure align to the values espoused by leaders?

Through assessing the answers to the questions above, we can establish the degree to which integrity has been embedded in the consistent behaviours of our teams, and the effectiveness of leaders in supporting this outcome.

How leaders handle their missteps.

The final aspect of leadership to consider, is how to handle situations where a misstep has been made. When it comes to missteps that impact or impair perceptions relating to integrity, it is almost inevitable that the result is a loss of trust. This loss of trust may just be felt in those impacted, or it could occur more broadly amongst those we are charged with leading.

Trust is integral to a pro-integrity culture, so when the bonds of trust amongst a team or in a relationship have been impacted, an investment must be made to remediate this. This investment of time and effort should be underpinned by the following principles

- A commitment to the truth – when appropriate, efforts are made to be upfront and forthright regarding what has actually occurred.

- Transparency in accountability – leadership or others responsible for any mistakes are clear in taking accountability not only for their actions but for any and all consequences.

- A willingness to give – a proactive and genuine willingness to give advice, give time and give of yourself to those who have suffered for the lack of integrity in behaviours or actions.

A pro-integrity culture does not mean that no mistakes are made. However, it does mean that when they are made there are truths told, there is transparency in accountability, and there is an investment made to remediate any damaged trust. These principles, and the extent to which leaders have lived up to them, should be looked for when evaluating the impact of leadership in supporting the growth of integrity.

AUTHOR: SIMONE KNIGHT

World Quality Week – 11-15 November 2024

World Quality Week takes place every November. This global campaign raises awareness of the benefits of organisations taking a quality management approach to their operations.

This year’s theme is Quality: from compliance to performance. The timing couldn’t be better for those of us working with Federal Government. We’re now in Quarter 2, 2024-25, so we’ve had sufficient time settling into our Corporate Plans, we’ve finalised our Annual Reports and we are heading towards MYEFO. So how can our corporate documents lift and shift us to achieving high performance? Could a quality management approach be the solution?

Our Roles in Responding to Climate Change

One of our current challenges is how organisations are adapting to climate change. The Government’s push to net zero is also front of mind for many agencies. For those organisations certified or seeking certification under ISO 9001, there is a new requirement in the standard to consider the impacts of climate change as an internal or external factor. This amendment has been effective from 22 February 2024 and aims to integrate climate change considerations into management systems – not only quality management systems under ISO 9001, but also environmental management systems under ISO 14001 and work safety management systems under ISO 45001 (which are the three most widely recognised standards in the world).

Under ISO 9001 organisations are now required under clause 4.1 to assess the impact of climate change on operations to “understand the organisation and its context.” If climate change is identified as relevant to the quality system, it should be treated like other internal or external factors and included in the assessment of risks.

This imperative to address environmental concerns adds another layer of complexity to our operations and this of course, coincides with the Federal Government’s reporting requirements regarding climate change, including the Commonwealth Climate Disclosure requirement to publicly report exposure to climate risks and opportunities and actions to manage them. Under this policy, Commonwealth entities and Commonwealth companies must disclose climate-related information in their annual reports.

An additional amendment to ISO 9001 reinforces this through a new note to clause 4.2 that states “relevant interested parties can have requirements related to climate change.” While this note does not impose extra requirements, it clearly links the ISO 9001 standard to the requirements of interested parties, such as the Government, regarding climate change disclosures.

With that in mind, we should consider how quality management principles and methods allow organisations to respond, creating a culture of process improvement. Quality management can be associated with tools, processes, controls and governance. These elements are all-important, but an organisation’s culture is what will nurture innovation and continuous improvement to achieve high performance. Quality principles and methods not only ensure compliance but also foster learning and agility, to allow organisations to adapt to change more effectively and drive performance excellence.

Act Now

While some organisations will need to be more agile than others when it comes to adjusting for climate change impacts and fulfilling reporting requirements, there are some simple things you can do now to assess your organisation’s position:

Consider how climate change may affect your organisation

It’s important to consider both direct and indirect implications. Some direct implications include changes in weather patterns, rising water levels and government-imposed restrictions that may have an impact on the goods and services that are outputs of your organisation. You may need to adjust how you support human resources, change your physical infrastructure, and start capturing data about climate change related performance.

Indirect consequences may include the introduction of new technologies, shifts in the behaviours of the public and the potential for business disruption as a result of changing weather patterns. You may also experience changes in your supply chain and consumer behaviours.

Assess your risks and opportunities

Remember that not all impacts of climate change need to be negative. As we said above, a quality approach encourages innovation, and climate change may well present the catalyst for designing new practices that create efficiencies and take advantage of new technologies. It may also be an opportunity for a reputational boost for your organisation. Over three quarters of Australians[1] (78%) are worried about climate change and extreme weather events in Australia. Climate action by your organisation may have a positive impact on the way the public responds to your organisation.

Develop an action plan

You may need to update your policies and procedures (including to cover the requirements of clause 4.1), develop and implement training for personnel, incorporate climate change into the governance of decision-making, put in place practices to enable the capture of climate change data, and implement reporting procedures.

If your organisation is ISO certified, auditors may seek evidence that you have considered the issue of climate change. To provide this evidence, we recommend you demonstrate climate change consideration in your organisation’s documentation including by documenting the actions you are taking (your action plan), be transparent with internal and where appropriate, external, audiences about those action plans and ensure they are maintained and kept up to date to reflect the current state of your activities.

Recognise that climate change will involve continuous improvement

Risk assessment and actions relating to climate change impacts will not be a once-off activity. You may need to develop strategies and build performance targets that are reflective of an increasing maturity as your organisation learns to adapt to climate change.

Drive performance

Here are some top tips from the Chartered Quality Institute[2] to harness a quality management approach to drive performance:

- Embrace innovation: Don’t just meet compliance standards; leverage quality management to drive innovation and stay ahead of the curve.

- Manage risks proactively: Identify and mitigate risks associated with digital transformation and other strategic initiatives to ensure long-term success.

- Focus on sustainability: Integrate sustainability into your quality management practices creating products and services that are environmentally and socially responsible.

- Promote a learning culture: Encourage continuous learning and improvement within your organisation to adapt to changing market conditions and customer needs.

What’s Coming Next in the World of Quality Management?

Some emerging quality management issues which may well form part of the next amendment to the ISO standard (expected for 2026 implementation) include:

- A change in the focus on customer satisfaction to a broader concept of ‘customer experience’;

- Integrity and ethics in decision-making;

- Increasing customer expectations of organisations to deliver sustainable innovation where promoting good operational governance, assurance and improvement will support delivery safely and confidently; and

- AI, digitalisation and automated decision-making, which present both opportunities for performance enhancement and risks for many organisations

Why Choose Sententia?

At Sententia Consulting, we believe that quality management provides organisations with a framework that is valuable in supporting improvements in operations to achieve high performance.

We understand that not all organisations are pursuing ISO certification, and we take a pragmatic approach to support organisations to implement quality practices that are fit for purpose. We can help you stay compliance and future-ready with our expertise.

If you are interested in learning more about how Sententia can help you, please see www.sententiaconsulting.com.au or email us at sententia@sentcon.com.au.

[1] www.climatecouncil.org.au from a recent survey conducted in March 2024.

[2] https://www.quality.org/WQW24

AUTHOR: BRIONI BALE

The Australian public service supports Government to develop, implement and update Australian policy which can have population-wide impacts. Project managing policy change can be a challenge due to the complexity, tight delivery timeframes, inclusion of many stakeholders and the high sensitivity to risk, uncertainty and changing political environments. Outputs stemming from policy change are often less specific and are more focused on longer-term outcomes. How policy outcomes will be achieved can be unclear and can continue to change as the policy is developed, negotiated and agreed to by Government. The implementation of policy is typically more contentious or polarising than other types of change.

Good project management is essential to ensure successful delivery of policy outcomes, which can be significant, challenging to deliver and may require a different project management approach, when compared to other types of large-scale projects. This article explores how policy project management differs and provides techniques that can be used to improve successful delivery of policy in Australia.

Why is policy project management different?

- When compared to other types of projects, policy projects typically attract broader stakeholder interest (Ministers, their staff, government agencies, industry, industry bodies, consumers and, the public more generally) due to their potential for broad population impact. Other project types have more limited and specific stakeholder interest. There may be a large number of stakeholders, but the variety is generally less.

- Communication is important on all types of projects, but effective communication is essential in policy projects to gain support from stakeholders, influence public opinion, and ensure successful implementation. Communication in other types of projects tends to be more focused on internal updates, user engagement and marketing type activities.

- Developing policy involves extensive research and analysis (data collection, impact assessments and evaluation of pre-existing policies). Evidence-based decision-making is crucial to show the need for the policy, as well as supporting the development of sound policy. Research and analysis may also be important in other types of projects but it’s generally market research, technical feasibility, or user experience.

- Policy projects must consider legal and regulatory frameworks, compliance issues, and the potential for legislative changes. Public consultations are often necessary and there is generally always a need for some sort of legal advice. Where legislation is part of the policy, Parliamentary processes must be followed, which can take considerable time. Non-policy projects may need to consider regulations and compliance but typically not to the same extent.

- Implementation often involves multiple phases and can include pilot programs to better understand impacts. Specific evaluation points can be established to measure the effectiveness of the policy to allow for adjustments if needed. Other project types focus more on project roll-out, user adoption and iterative improvements over time based on feedback.

- Policy projects are generally funded by public money or grants, which comes with an increased need for transparent reporting and accountability to ensure value for money. Formal policy authority from Government is required. Other project types are funded by private investments, internal budgets, or revenue, with different accountability mechanisms.